Harmonic & Structural Analysis of Preludes 1 & 3 of the Cello Suites by J.S.Bach, BWV 1007 & 1009Return to the Homepage of Georg Mertens

Violinist Gustaw Szelski

1950 - 2021

&

The Jenolan Caves Concerts

Youtube channel -

Solos, Duos,

The 6 Bach Cello Suites

Cello Issues

Poems by

Georg MertensPoems by Han Shan

(Cold Mountain)

edited

by Georg Mertens

- Japanese- Chinese

- Korean

- Hindi

- i - Russian

- i - Turkish

- Greek

- Espanol

-

French- Italian

- Polski

- Hungarian

- Portuguese

- // - Arabic - //

Harmonic & Structural Analysis of Preludes 1 & 3 of the Cello Suites by J.S Bach, BWV 1007 & 1009

Copyright for this page by Georg Mertens

(c) 2013 Katoomba / Australia

Quotation and references for the use of any material from this site needs to state the author of this website.

Any use of material of this site for publication is only permitted after arrangement with the author.

Contact:

email: georgcello@hotmail.comI have so often been contacted with the question regarding anharmonic analysis of Prelude 1 and 3 of the Cello Suites!

As interesting as this may be, I can't emphasise enough, that such an analysis does not help much in the way of interpretation!

I enjoy to do an analysis like doing a hobby - but the practical effect is as little as pulling a poem apart, which does not help reading it convincingly or understanding it.

For interpretation I strongly recomment to consult rather the chapters below on "dynamic mapping" - diagnosing the inherent elements, which show us the inner guidelines,

which make a composition transperent and beautiful in the sense, that the artwork is understood and can be communicated to the listener.

** Click here for an Analysis of the Bach Cello Suites according to the early manuscripts and prints.

This Analysis will help more to understand the interpretation of the Preludes than a harmonic analysis (click here).

CONTENTS:

ABBREVATIONS and TERMINOLGY used in the Analysis (click here)

_____________________________________________Prelude of Cello Suite I (click here)

Prelude of Cello Suite III (click here)

Overview of the harmonic structure of the dance-movements in the Cello Suites (click here)

History & Characteristics of the Prelude (click here)

______________________________________________* Point of interest:

For the hitherto unknown B - A - C - H citation in 4 movements of the 5th cello Suite click here

ABBREVATIONS & TERMINOLOGY used in the ANALYSIS

In my analysis I firstly state the key of the harmony and the specifics of the chord / triad.

Secondly I state the function of the chord within the key of the piece.

(Another way of identification also used would be to identify the chord as steps of the scale, like I and II according to the key of the piece.

I decided to use rather the function like Tonic and Dominant, even if it gets complicated, because in my own perception this is what I hear.

E.g. An analysis like II minor - or II major does not mean much; but the Dominant of the Dominant can be heard, and so can the relative minor to the Subdominant.

The functional analysis relates also to the Baroque way of composing and hearing Baroque music. I would analyse Debussy differently.

I am aware that there are these two ways of analysing.KEYS & CHORDS

C: - C major triad-arpeggio / scale (or parts of it indicating the key)

D: - D major triad-arpeggio / scale (or parts of it indicating the key)

etc.Cm: - C minor triad-arpeggio / scale (or parts of it indicating the key)

G7: - G major 7th chord-arpeggio / scale (as Dominant 7th chord to tonic C major)

G7: - G major 7th chord-arpeggio / scale with the 3rd in the bass / !st Inversion

3G7: - G major 7th chord-arpeggio / scale with the 5th in the bass / 2nd Inversion

5

etc.

If the capital letter indicating the chord is crossed out, it means the root note of the chord doesn't appear.

FUNCTIONS

(T): - I - Tonic

(RmS): - II - Relativ minor to Subdominant (of Tonic)

(RmD): - III - Relativ minor to Dominant (of Tonic); this is a minor key

(S): - IV - Subdominant

(D): - V - Dominant

(Rm): - VI - Relativ minor ( to Tonic )

(DD): - II - Dominant of the Dominant

(DRm): - III - Dominant of the Relativ minor (to the Tonic) - this is a major key; Dominants are always major unless stated specifically

(SD): - I - Subdominant of Dominant, in this case (which is the overall Tonic, but in this particular case the Subdominant function overrides the impressiononor function of it being the Tonic)

Pedal Point - indicated in blue

The Pedal Point might be part of a chord and be integrated, but might at other places conflict with the chord. In the analysis the chord is described not considering the pedal point..

The pedal point takes an interesting place adding colour by participating and not participating in the chords.Transitions - indicated in red

- usually within the last beat before a new bar with the new harmony.ARROWS - The harmony has a Dominant character leading to the (resolution in the) next bar. The resolution might be temporary and another resolution may follow.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

For my arrangements & compositions for cello, 2 cellos, cello & guitar on sheetmusicplus click on icon

PRELUDE of SUITE I

BACH PROJECT DONATION

If you wish to support the Bach Cello Suites research, you can do so.

New videos, research are now first published on my patreon forum.

A donation will entitle you to have access and be notified of new videos

on the Bach Cello Suites - research, recordings, talks,

lessons to the movements and make you a member of the cello course

including the CELLO ISSUES series.

To have a look, click below, go to "Collections":

https://www.patreon.com/c/georgcello/

STRUCTURE

Prelude 1 is written in 2 distinctive parts.

Part 1 extends from the beginning to the middle of bar 22, the note D marked with a pause.

Main feature of Part 1 are arpeggios.

The arpeggios are spread over 3 strings and the harmony is established within the first 3 notes.

The pattern as introduced in the first 8/16 in bar 1 is the most common pattern.

The unit of 8/16 is repeated in the second half of the bars, sometimes including a bridging note to the next chord.

The bridging notes or transitions occur within the last beat before the new bar of the new harmony (bars 4, 5, 7, 12) with the exception of the leading note to the last note of Part 1 in bar 23, which is on the 2nd beat.

However, Bach alternates frequently one bar of aprpeggios with one bar of a melodic line using chords and parts of scales, which are used as transitions between harmonies.

Such pairs of bars alternating arpeggios & melody we find in bars 4 & 5, 6 & 7, 8 & 9, 11 & 12, 13 & 14.

When intrepretating we bring the first 8/16 more out, as they are the new statement introducing the new harmony; the second group 0f 8/16 (9-16) should be treated like a typical Baroque repeat and played softer, close to an echo of the former (in several edition and also the manuscript of Anna Magdalena and "D" the secend set of 8/16 falls on an V (up-bow).

We find only 3 continuous sets of arpeggio bars in the whole Prelude, bar 1 - 4 and 15 - 19 of Part 1, both ending in exactly the same note pattern of a G major chord. Similar are the last 4 bars of the Prelude with a 3 bar arpeggio, also ending in a following G major chord. We find in all these 3 passages also a pedal point, G in the sections in Part 1, D in the section in Part 2.

Part 2 extends structurally from from the A after the D marked with a pause in bar 22 to the end.

The part of bar 22 belonging to Part 1 is written in an arpeggio, the last 2 notes of Part 1 are already in a scale movement of semitones, leading to the character of Part 2.

The Part of bar 22 after the pause is already distinctly Part 2: a straight scale upwards, the first in its length in the Prelude.

Main feature of Part 2 are scales; arpeggios appear rarer, mostly during the 1st and 3rd beat, and in bar 28 also on the 2nd beat.

When arpeggios appear, they often state for short the harmony / chord, which is then followed up by the corresponding scale - the same harmony is expressed firstly via a triad and secondly with a scale.

In the first half of Part 2 we find straightforward scales or parts of scales (bar 22 - 30/31), whereas in the 2nd half Bach uses consistently a pedal point alternating with the melodic line (bar 31 - 38 and even continueing from 39 - 41).

The last 4 bars are leading back to the repeated arpeggios in the style of part 1, a bit like a recapitulation in the Sonata form, which developed later.

In difference to the beginning of the Prelude the arpeggios are written in the mirror iamage from the beginning, going from the 1st to the 3rd string instead of the 3rd string to the 1st.

Comparison:Prelude 4 (in Eb major) is composed using the same structure as Prelude 1:

Part 1 are arpeggios, in the first section the pattern is set in bar 1 and repeated in the following bar.

Part 2 is based on scales, distinctly different from Part 1.

The end is a reminder of the beginning, only in this case llterally with a coda like ending - even closer to the later Sonata form as Prelude 1.

HARMONYKey: G major

PART 1 (bar 1 - 22)

[ For the sake of clarity I indicate the harmony excluding the ornamental note beneath the highest note,

e.g in bar 1 I don't consider the "A", as if the music would have been noted like:

Why did Bach didn't write the figure like that? Although harmonically this notation is correct, Bach wouldn't have been able to determine the bowing and the exact execution of the rhythm he had in mind.]

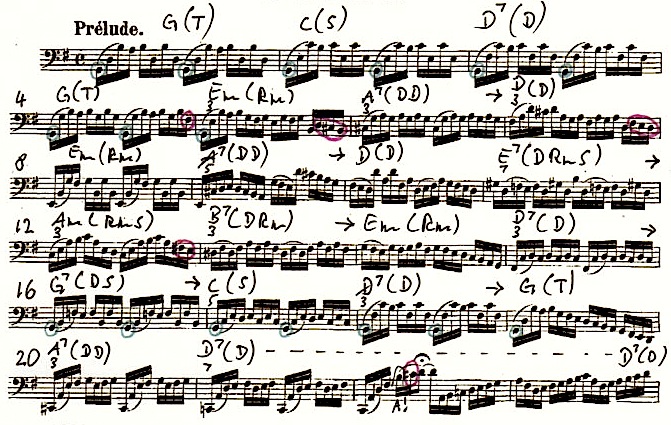

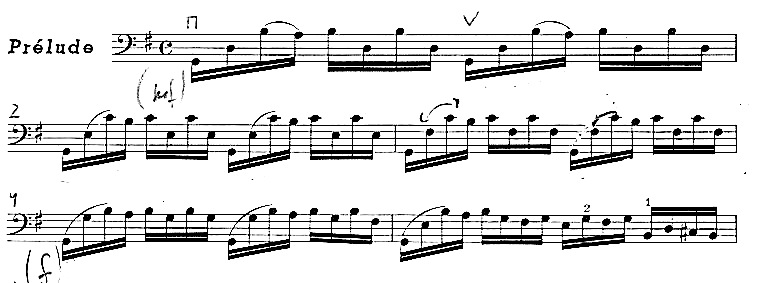

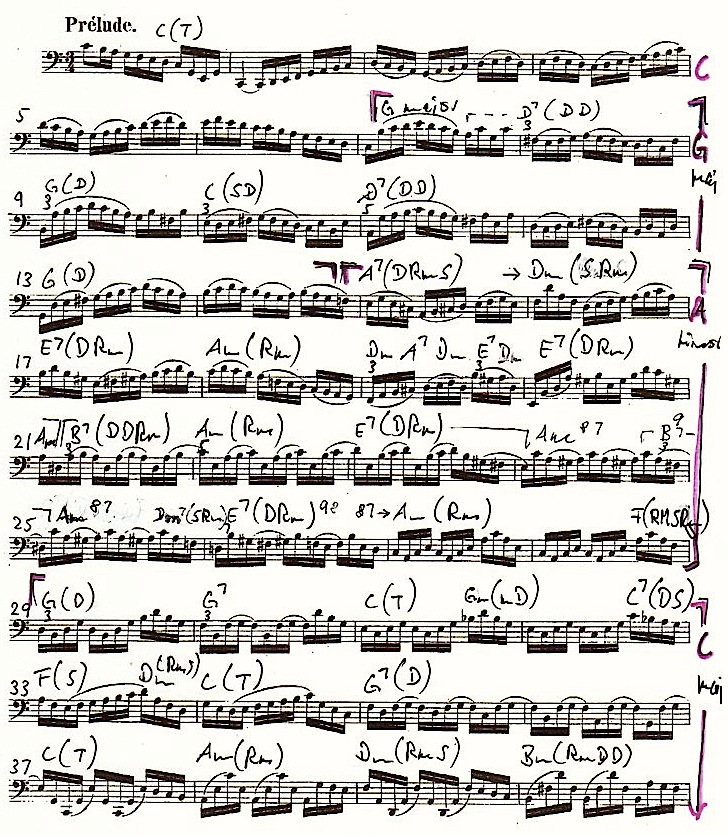

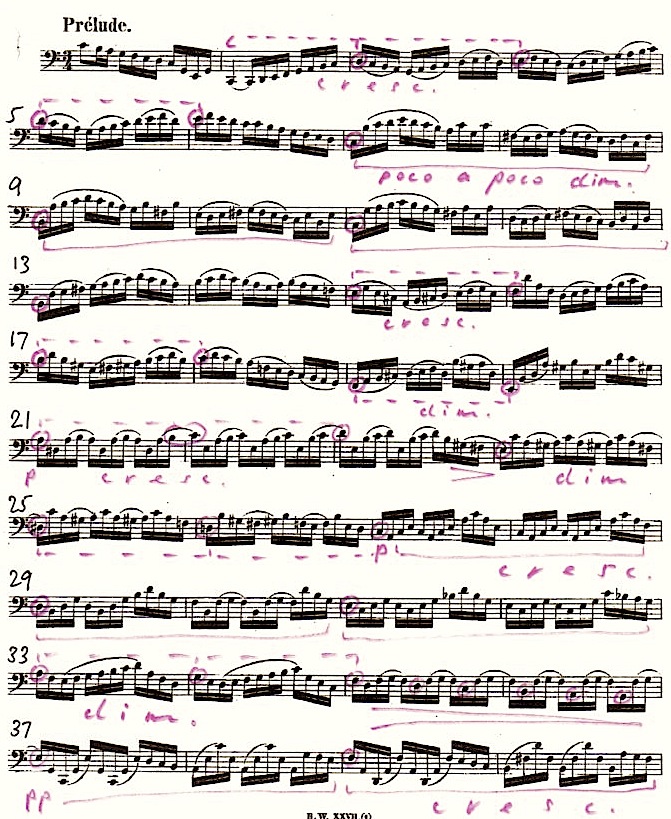

Description:In the print below key and function are handwritten in.

The key of the triad / chord or scale is written first.

The function appears in brackets after the chord description (for abbrevations see above).

A Pedal Point is circled in blue.

Virtually throughout the piece harmonies change with the bar lines (if harmonies change).

At several places the notes before the bar line lead into the change of the new harmony (these notes are circled in red)

At several places Bach introduces a chord with a Dominant function not relating or only little to the bar before, yet leading to a solution in the following bar.

I indicate this relationship between the Dominant character and the following bar with the solution with an arrow.

The Harmonies of Part 1

Pedal points are circled in blue. Transitions are circled in red.

The key of the harmonies is written first (like 'G' for G major) followed by the function (like 'T' for Tonic)

Arrows indicate that the Dominant character is resolved in the following bar. For abbrevations see above.

[Print: Doerffel 1879]Bar 1 - 4 :

A straight forward G - major Cadence (Tonic: G major - Subdominant: C major: - Dominant: D major 7 - Tonic: G major), establishing the key, before adventuring into an individual avenue.

These first 4 bars are united by the pedal point G (indicated with blue circles), which continues through to the first note of bar 5.

This is also the point, where the individual journey begins, prepared by the first transitional note in the Prelude, last note of bar 4 (indicated in red).

Transitions are all within the last beat befor the new bar of the new harmony (bars 4, 5, 7, 12) with the exception of the leading note to the last note of Part 1 in bar 23, which occurs on the 2nd beat.

The bars with a scale character function also as a transition, only more extended (bars 9, 10, 14, 19).The "cadence circle" at the beginning of Prelude 1 compared to "The Swan" by Saint-Saens

This straightforward cadence at the begiining of a piece is common from the Baroque period to the Romantic - it manifests for the listener where you stand harmonically.

As a student of mine pointed out, she thought we could play "The Swan" together with Prelude No 1, they seemd harmonically so similar! The student is very talented, has a good ear, so I took the idea seriuosly - and interesting enough Bach and Saint-Saens use the same harmonic development at the beginning: the pedal point on G with the cadence placed on top. As an experiment I changed the rhythm of the Bach Prelude from 4 to 3 (6) to make it fit - and to my surprise it sounded like meant to be. In the following part I changed the "Bach - part" fitting the harmonies of the swan. Here is a recording:

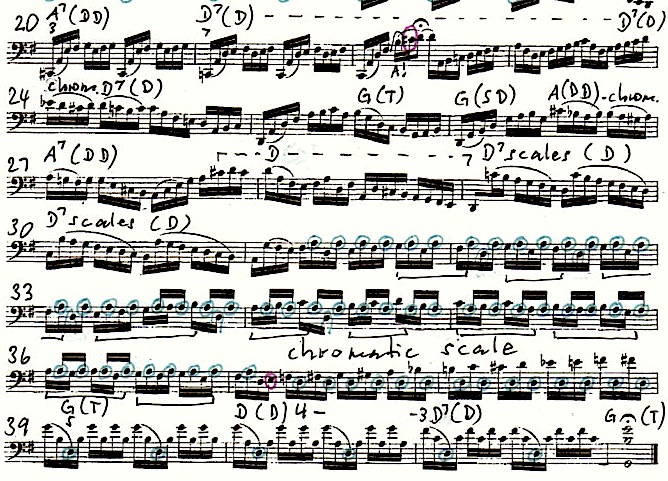

Part 2 extends structurally from the A (after the D marked with a pause) in bar 22 to the end.

But harmonically the D7 chord appears already in bar 21 and continues to dominate either as harmony, scale or pedal point from there on to the second last bar.

The D and the D7 chord dominates the whole 2nd Part, from the start of Prt 2 throughout to the second last bar.

This domination of the Dominant D appears as pedal polint, chord or scale and is also the base of the short melodies and sequences.

The harmony modulates only for a very short period to D major: from the C# in bar 28 (last 3/16) to the D on the first beat in bar 29.

This shift to D major as a temorary Tonic is prepared from the change of function of 2 following the G major chords:

The G major harmony in the second half of bar 25 is this of a tonic and changes at the bar line to bar 26 to a Subdominant function in the temporary key of D major.

The Pedal Point D

Descending scales from bar 29 to 31 lead to a large section with the pedal point D, extending to the end except the last chord.

From bar 31 to 37 the pedal point D is overshadowed by a second pedal point: The Dominant 'A' , sitting strictly a fifth above the D pedal point.

For the length of 2 bars, 35 & 36 the D does not appear, preparing the listener to the more frequent occurence form bar 37 on, thus avoiding getting tired of hearing the D throughout the second part.

Similar the D is missing in the last chord - although belonging in to the harmony and belonging to the other end of the fame, bar 1 - freeing the listener of having to listen to the D in the last chord again.

During this section bar 31 to 37 segments of scales and 3 note melodies are set as repeated phrases (bar 31 / 32) or sequences (bar 35 / 36).

Although we might see these elements as 'just' structural, they implement dynamics especially at a time, where dynamics were not written in and the player had only a guide line regarding dynamics from within the composition itself.

Which dynamics were implied is explained below in the section: dynamic mapping - Hidden and open scales.

The Harmonies of Part 2

Note the double Pedal Point in bars 31 to 37 (indicated in blue)

[print: Doerffel 1879]Dynamic Mapping: Hidden and open scales

Up to now all knowledge of pedal point and harmonies did not affect our interpretation. It rather gave a name to a sound, to which reacted already naturally and have formed our character of sound, or playing forte and piano, independent if we found the right name or not.

As strange as it sounds, the knowledge of harmony effects interpretation as much as the kind of paper we write the information on!

It starts to help us only, when we wish to write music ourselves - and want to understand what can be done - or when we transcribe to another instrument on which we add or leave out notes, which of course has to be done with an understanding of the harmony (although our ear and a good taste might replace to a good deal the formal analysis).

This is different with hidden and open scales.

A scale has a clear directio., Except in rare cases, a scale ascending points to a crescendo, a scale descending to a diminuendo.

Discovering hidden scales gives the shaping of dynamics a larger scale:

We must play the notes belonging to a hidden scale in a way that the listener can follow the existence of the scale, point these notes out - strong or subtle.

This gives suddenly the piece a formal structure, through which a good player acts as a tour guide to the listener.

The performer explains the composition withoutb using words - explains the structure by simply playing the underlying structure.

Of course it adds clarity and beauty to a performance.

In particular this means:

the circled notes in bar 23 crescendo to the ONE in bar 24, the following 2 circles indicate a diminuendo.

Bar 26, 27 - the circled notes indicate a diminuendo.

Bar 29 starts with a convincing "C", followed by a diminuendo to bar 31, where a new line starts from the D.

The movement is interrupted by a repeated sequence (2nd & 3rd beat of bar 32); we have here statement, echo & reinforcement.

Bar 33 starts a scale in G major, from D to C ( as D7) but actually continuing to the D - from where a repeated sequence (see bracket) in half bars (including the D pedal point) leads gradually down.

I recommend to support the sequence with a sequential fingering; it helps the memory and brings more clarity of playing.

Having arrived in piano, a chromatic scale up indicates the last great crescendo before remaining in a full sound indicated by the width of the chord and the minimal up and down movement.

Dynamic Mapping: Hidden and open Scales in Part 2 (indicated in red). [print: Doerffel 1879]

If played well, the listener can easily follow the indicated "hidden scales".I included on this webpage a general guide on "dynamic mapping".

This "map" gives us the dynamic instruction, which in later times has been written out by the composer, like forte and piano.

But in Baroque times this was not common - and to some part the understanding of the structure - usually polyphonic - effects the interpreation in a way, that can't be described by an overall dynamic as the different simulaneous parts have different dynamics and like here, single notes are important to "point out" in a careful way, which can't be simple labelled with a dynamic.

The interested reader or player can read more on this by clicking here on: Dynamic Mapping & Phrasing (click here)Dynamics

Very rarely I write specific dynamics in.

The performance, if private or public, depends very much on the mood of the day, the nature of the performance space and the audience.

This is particularly true for the Preludes, the more atmospheric introductory movements.

The dance movements should vary anyway in the repeats.

Defined dynamics lead to play just what is written without understanding and having a sensitivity to the situation.

I find, too many "readers" (particularly players, who don't play by memory) find in written dynamics a way to play a piece like a study, with little feeling and little understanding.

I try with my articles and graphps as much as I can to get away from just copying what is written, but understanding and experiencing - living - the music every time anew we play it.

Also, the historically later developed way of writing dynamics in relies on, that all parts have for a worthwhile period the same dynamic.

In Baroque interpreation the dynamic line is much more complex as to simply write an overall average dynamic in (which might be a reason that composers didn't become convinced it might be advisable to write "a dynamic" in).

A good interpreation distinguishes the different dynamics of beat 1 and 2, of bass and top melody, of so many factors, that writing it in is either too complicated or fails the purpose -

and as mentioned, in repeats we should vary, on different days and in locations we should play differently - intergrated with time and space.____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

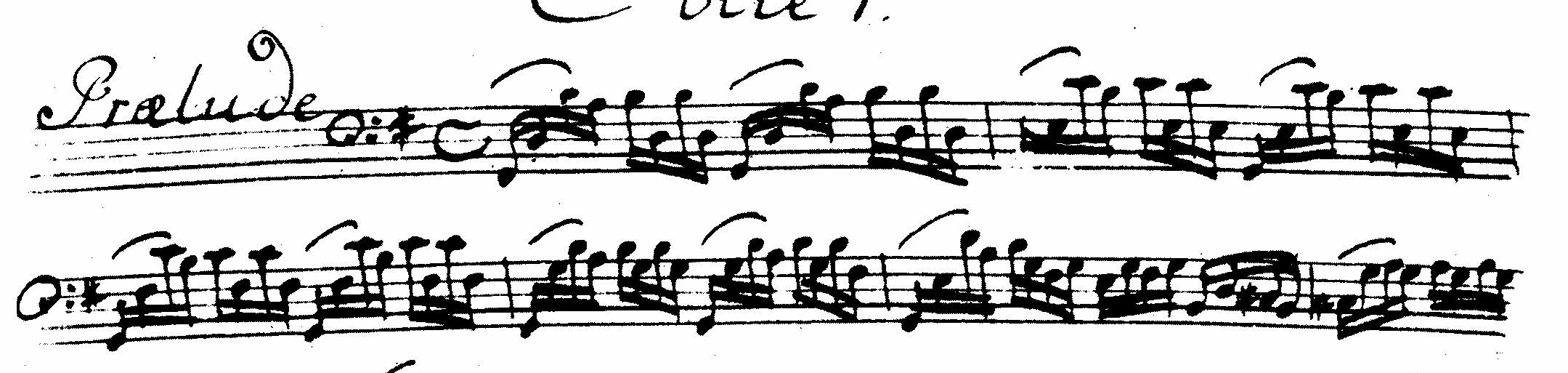

The following is an excerpt of the critical Analysis of all movements of the six Cello Suites (Bar 1 - 4 of Prelude I )

BACH PROJECT DONATION

If you wish to support the Bach Cello Suites research, you can do so.

New videos, research are now first published on my patreon forum.

A donation will entitle you to have access and be notified of new videos

on the Bach Cello Suites - research, recordings, talks,

lessons to the movements and make you a member of the cello course

including the CELLO ISSUES series.

To have a look, click below, go to "Collections":

https://www.patreon.com/c/georgcello/

PRELUDE I

Bar 1 - 4

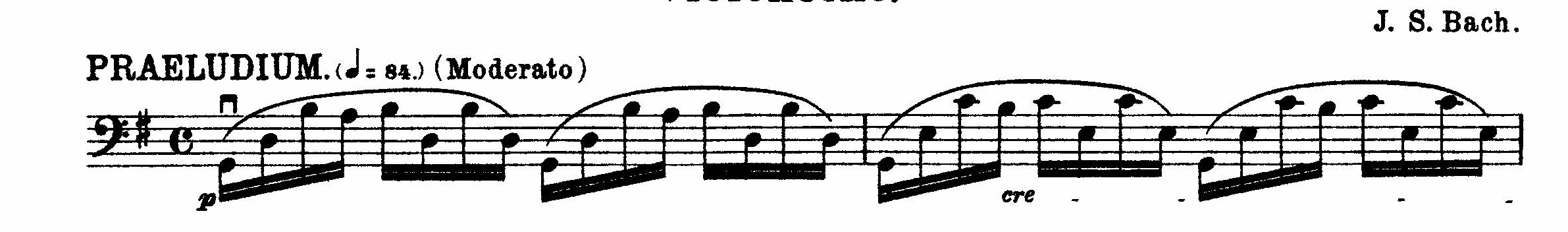

Bowings in the manuscripts and prints:

Most early sources show the same bowing for bar 1 - 4. I chose here the following early sources with this bowing:

Manuscript (C) c 1750-1800 / the first Dotzauer edition 1826 / the first Bach Gesellschaft (bach society) edition by Doerffel 1879.

Many cellists today chose this bowing including Rostropovich, Yoyo Ma and myself.

Manuscript (C) c 1750-1800

First Dotzauer edition 1826 (left) - First Bach Gesellschaft (Bach Society) edition by Doerffel 1879 (right)

The earliest printed edition by Janet de Cotelle c 1825 however shows a start with four 1/16 slurred. We find this bowing also in manuscript "D".

I assume this bowing is not the original one, as it hasn't been taken up by anyone except the first French edition.

It is however interesting, especially in comparison to the manuscript by Anna Magdalena.

This bowing puts the beginning of the bar on down bow, the repeated phrase in the second half of the bar on up bow.

Naturally the repeated phrase in the second half of the bar in up bow will sound softer, bringing out the change of harmonies, which always occur in the first half of the bar.

Although technically more awkward, this bowing sounds more musical, avoids the rattling down of repetitions without dynamic change, as people would do when they first play it through.

I assume this bowing goes back to a correction - and as we will see perhaps by Bach himself - who might have thought he is getting tired of hearing the beginning of the Suite in a way he hoped it wouldn't sound.

As mentioned, interestingly enough the first 4 bars of Anna Magdalena's manuscript set the beginning of the second half of the bar in up bow -

( the modern-bow Hugo Becker edition also slurs all eight 1/16; this might be part of the attraction of Becker's bowing).

Janet de Cotelle (left) / manuscript "D" (right) - in bar 3 he added one slur too much; during his time "whiteout" did not exist. A mistake remained a mistake unless blacked out.The manuscript by Anna Magdalena Bach.

Anna Magdalena's manuscript shows in the first 4 bars different bowings to all other editions. Just out of interest I performed the Prelude a few times with this bowing.

It is awkward, seems to go against a natural feeling of flow, especially in bar 2 and 3, but it brings effortlessly some dynamic elements out:

The first 2 notes are separated. This gives us the opportunity to lengthen the first note as much as we like without experiencing a shortage of bow, which encourages to play out the introductory G - we know this introductory statement of the G by Pablo Casals although he used often the Hugo Becker bowing.

In bar 2 and 3 only the first note is single followed by a slur of two. This takes the emphasis away from the top melody and gives altogether a somewhat weaker feeling as if bar 2 and 3 are meant piano.

The bowing of only two 1/16 slurred (instead of 3) has another side effect: when we play a down bow on the first beat, we will end up with an up bow on the third beat.

This lets us naturally play the second part of the bar even softer, pianissimo - the repetition of the first half, creating an echo like effect as Baroque performers would have played the repetition of a phrase.

We come now to bar 4, which for the first time has the first 3 notes slurred.

This has an interesting effect: even without intending to play dynamic differences, this bowing emphasizes bar 4, makes it sound fuller, quasi forte.

This would mean that from the perspective of intensity we have bar one standing there with the fully expressed first note G, the key note, followed by a standing back bar 2 and 3 in piano, followed by bar 4, fuller sounding than all bars before.

Could this be intended? Looking at the harmonic structure it makes sense:

Bar one states the tonic G major, bar 2 leads us to the subdominant, bar 3 to the dominant and bar 4 arrives again at the tonic - with the open G always kept as a pedal point.

I call the introductory cadence "the city circle" after our underground train - before you can travel to an individual destination you have to go through the circle of the home cadence.

Quite literally Bach does the same in the first Prelude of the "Well tempered Clavier".

Anna Magdalena's bowing is different than all the others, but it is musically so convincing, that we can't discard it as a mistake or one of her misunderstandings of the bowing technique of string players.

It is also very accurate written, with a precision as if being very aware of every slur drawn.Why would Anna Magdalena's manuscript be different than all the others?

We know, manuscript "B" is older, and starts with 3 notes slurred.

We assume Bach's manuscript had the first three 1/16 slurred, as all early copies and prints show the same bowing (except manuscript D and Janet de Cotelle).

I can't imagine Anna Magdalena would have changed bowings without an authority to do so.

So I can only imagine that Bach himself contributed to this new and unusual bowing.

Anna Magdalena's copy is written quite some years after Bach's original, and copies existed already, and he had heard the result of his bowings - and Bach seemed to be not happy.

He put forward a new idea avoiding a thoughtless sight reading; he confronted the player with a bowing you have to read careful and dynamic structures, which followed naturally when you just followed the bowing.

I assume manuscript "D" is an easier variety of this new idea, also dated later, starting with 4 notes slurred and putting therefore the second half of the bar starting with up bow, softer than the first half.

Anna Magdalena's manuscript (left) / Gruemmer's print of Anna Magdalena's edition (right)The change of the construction of the bow by Tourte from a Baroque bow to our bow today, which gradually came into fashion between 1800 - 1820, encouraged the idea of longer slurs.

The first addition of slurs was introduced by Gruetzmacher, modified by Casals into a more even division, easier for today's bow, then extended to virtually a love affair with slurs, slurring everything as much as possible by Hugo Becker.

Today most players use his edition and the sound of slurs is for most players today the predominant sound character of the Prelude of Suite No 1.

(We find the identical dynamic instructions in both editions, Gruetzmacher and his student Becker)

The first Gruetzmacher edition 1866 (left) / in my handwriting underneath the Casals bowing / (right) The Hugo Becker edition 1911 by Peters, IMC and others.

We can see in the Gruetzmacher edition for the first time larger bow divisions, a preparing step to the Casals edition and finally 8 slurred by Becker.Well, how should we play the start of the Prelude, given all these options?

The answer is, the choice of bowing is really not essentially the most important thing, but once we choose to start with a bowing, we need to be consistent, that it doesn't end up unclear and messy.

Bowing has a lot to do with comfort, a personal taste and also the response of our particular instrument.

The essence of an interpretation lies rather in the understanding of the composition and bringing out a concept so that the listener can hear it with clarity.

Where do we find the concept?

I recommend playing through the different editions. Each edition will bring out different qualities.

For me playing through the bowing of Anna Magdalena / Gruemmer was the most enlightening one:

Without even trying the start of bar 1 will be strong. Each first half of a bar will be stronger than the second half - the second half is a bit like an echo;

from a performers point of view: what has already been said doesn't need to be trumpeted out again.

What's new is always more interesting; from a Baroque performers point of view: the literal repeat of a phrase is always played softer - exactly the same thing.

In bar the arpeggio sounds full, forte, leading over after the introductory cadence to the now starting individual development of the movement.

Every interpretation should and can have this dynamic development, independent of the choice of bowing.

The somewhat sudden step to the forte in bar 4 is known as "step dynamic" a frequent feature in Baroque music.

Instead of a gradual crescendo (as recommended by Becker) the dynamic change happens rather sudden, in steps (These "steps" occur naturally on the organ or the harpsichord, which can not play crescendos).

Exactly the same step happens in bar 18 using the same change of bowing pattern.

We come to the conclusion that Becker's dynamics are rather out of style for Bach.Although most historians believe that Anna Magdalena is the most reliable source as she must have copied straight from the original of her husband

(Bettina Schwemer, editor of the Baerenreiter edition recommends to follow Anna Magdalena just because of this reason) no edition except Gruemmer/Doblinger bothers about her bowing.

The Kurtz edition even shows the manuscript on the right side and without any apology shows on the left side unrelated bowings without explanation.

Why does practically no one follows Anna Magdalena? Firstly it seems that tradition counts. Once people are used to something, they don't want to give it up (see also bar 26).

Secondly when a majority of editions show the same bowing - 3 slurred - editors seem to find it hard to break the tradition.

Anna Magdalena is the only one with her bowings, they are unique.

For me they are on one hand very interesting and worth to play - as they seem to be guided by Johann Sebastian who improved the other common (his older?) version.

The person who recommended her bowings knew string playing in and out, it was not Anna Magdalena's ideas, as she did not know much about strings.

And this is probably the reason her copy is not taken serious enough.

String players think in the narrow logic of up and down. They can't escape, it is one of the most essential part of their technical thinking.

This thinking is ingrained and is the result of learning and playing. Anna Magdalena offends the rules of a string player too often.

As a singer she thinks in phrases, and if a phrase - marked 3 slurs - seem to sound nicer with 4, she writes 4, although the whole bow direction is messed up.

We also must not forget, that she did this work often after she had put to bed a part of 21 of Bach's children. I have not met many mothers who would have been able to do accurate work after having finished such duties!

Bettina Schwemer interestingly enough compares Anna Magdalena's copy of the violin Sonatas & Partitas to Bach's original, which we have today.

There are lots of misunderstandings and inaccuracies and I personally don't understand the recommendation to regard her bowings as the prime source of understanding -

because obviously she did not understand them, as interesting as the corrected passages are.

I feel we need to understand her copy as a duty or friendship copy for some one, but not a copy of an alert enthusiast, who is an experienced string player, as the author of manuscript "C" seems to have been.

As a summary it seems Johann Sebastian interfered only in some sections. These sections stand out as being firstly different than the other manuscripts and secondly as being marked by a capable string player.

As if they talked about the copy when Anna Magdalena wrote it out and he mentioned his new ideas.

He must have stood beside her and explained exactly what he meant as these new ideas stand out as correctly marked.

On the other hand the copy is on one hand clear - she had a very good handwriting, similar to Johann Sebastian - but she obviously did not understand the bowings and often they don't make sense.

A combination of manuscript "C" and her new ideas might come closest to the original and includes Bach's "revised edition" of bowing.Prelude No 1 is the last number of "My CELLO METHOD" Volume 4

BACH PROJECT DONATION

If you wish to support the Bach Cello Suites research, you can do so.

New videos, research are now first published on my patreon forum.

A donation will entitle you to have access and be notified of new videos

on the Bach Cello Suites - research, recordings, talks,

lessons to the movements and make you a member of the cello course

including the CELLO ISSUES series.

To have a look, click below, go to "Collections":

https://www.patreon.com/c/georgcello/

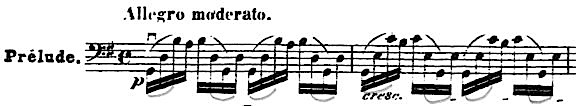

PRELUDE of SUITE III

STRUCTURE

Bar 1 - 6 : Introduction, using exclusively scales and triads in C major, ending on C, first note of bar 7.

Bar 7 - 14 : two bar sequences in G major, the last unit leading into the following A minor part.

Bar 15 - 28 : based mainly on A minor.

The first 6 bars (bar 15 to including the first note in bar 21) are flowing scales or chords in groups of 4, each group on the beat..

In the following 6 bars (21 - 26) the unit of beat and group is dissolved and creates, which creates a different texture. Slurs are bridging 1/16 over beat and barline.

Another group of 6 bars follows (27 - 32), this time arpeggios with detached bowings, again a new texture.

In the middle of this group the harmony shifts from A minor to returning to C major, including its main chords with a sidestep to G minor.Bar 33 - 36 are an interesting transition, the first of these 2 bars reminding of the scales at the beginning of the Prelude, the second 2 bars reminding of the passage from bar 21 - 26 with overlapping bows to the next beat.

From bar 37 on the structures get larger:

10 bars of units of 2 bars follow (bar 37 - 44), rising gradually note by note and landing on the Dominant G7 with again a new bowin - originally with a Baroque bow 3 slurred starting on the beat - today commonly played with the whole group of 4/16 slurred, also starting on the beat.

This bowing continues for 16 bars, ending on the first note of bar 61.

In the following section Bach uses alternating bowings / groupings used before, finishing on the tonic root note C in bar 71.

Like in some of the Preludes, he returns to the chacater of the beginning, rising scales followed by descending arpeggios.

The last 10 bars (bar 77 - 87) form a dramatic ending led by the bass, which descends from F step by step to the C, where it rests as a pedal point to the end of the Prelude.

The dramatic effect relies on the rests (there is no rest in this movement before the 10th last bar), which makes one think, that the piece has maybe been written for a larger hall, where the silence of the rests is filled with the diminishing echo.

Interestingly enough - and to foster this idea - the last chord is only 1/4 with written out rests: finishing quite swiftly and wait for the sound to vanish until the piece has really ended.HARMONY

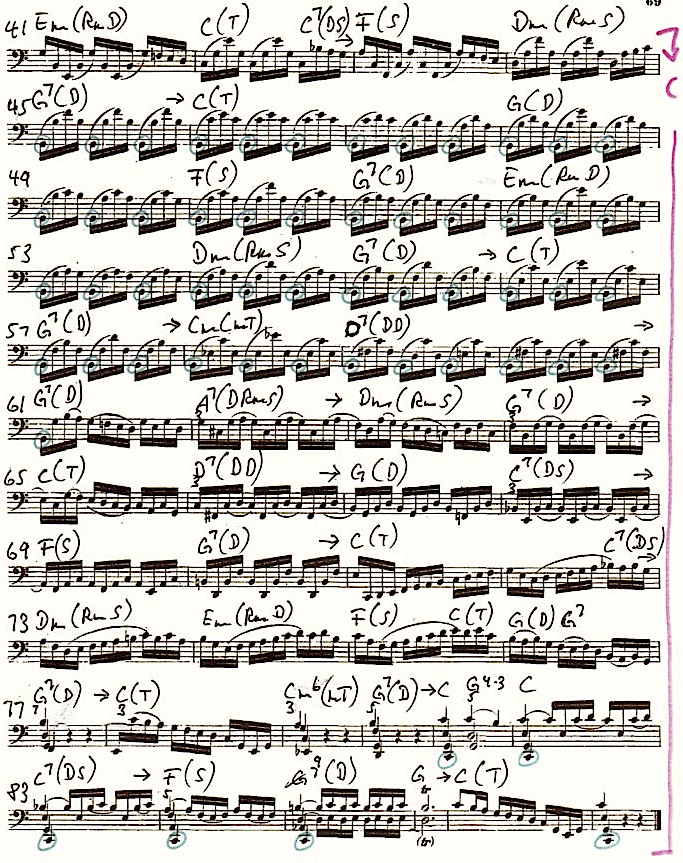

Key: C major

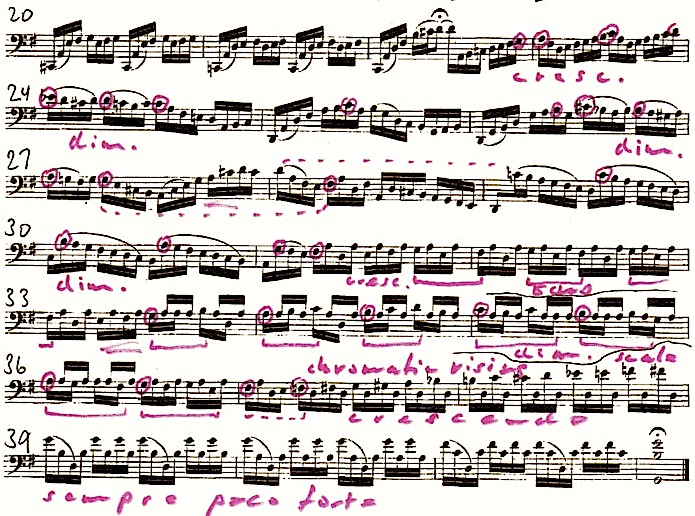

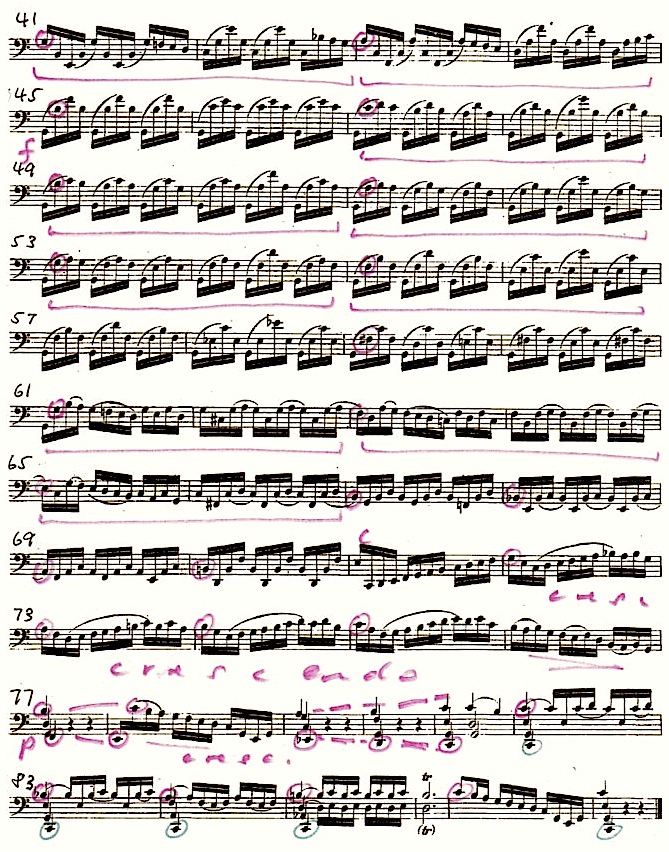

In the print below key and function are handwritten in.

The key of the triad / chord or scale is written first.

The function appears in brackets after the chord description (for abbrevations see above).

At several places Bach introduces a chord with a Dominant function not relating or only little to the bar before, yet leading to a solution in the following bar.

I indicate this relationship between the Dominant character and the following bar with the solution with an arrow.As mentioned under "structure" above, the Prelude starts with just scales in C major.

In this Prelude Bach ventures quite early into the Dominant key of G major - not the Dominant 7th harmony remaing in C major, as he does later during the peadl point G section.

A section in A minor follow, in which harmonies change very frequently, much more often than at the beginnings of a bar.

The flow or rather systematic progress thnough is not happening in the choice of key or harmony, but this music is composed another way around:

A more or less " hidden scale" or rather a scale or step like melody - not flowing from note to note - but set apart in distances from 1/16, but a beat apart, up to 2 bars apart determines where the music is going to.

The harmonies rather integrate into this system of scales that the scale follows the harmony, similar as in a chorale the harmony has to follow melody and bass and the melody does not follow some order of harmonies.

These "hidden scales also implemet a certain dynamic especially at a time, where dynamics were not written in.

The player had only a guide line regarding dynamics from within the composition itself.

Which dynamics were implied is explained below in the section: dynamic mapping - Hidden and open scales.

Harmonies, Functions and Pedal Points -

Pedal points are circled in blue.

The underlying Tonic of sections is indicated in red on the right hand side.

The key of the harmonies is written first (like 'C' for C major) followed by the function (like 'T' for Tonic)

Arrows indicate that the Dominant character is resolved in the following bar.

For abbrevations see above.

[Print: Doerffel 1879]Dynamic Mapping: Hidden and open scales

Up to now all knowledge of pedal point and harmonies did not affect our interpretation. It rather gave a name to a sound, to which reacted already naturally and have formed our character of sound, or playing forte and piano, independent if we found the right name or not.

As strange as it sounds, the knowledge of harmony effects interpretation as much as the kind of paper we write the information on!

It starts to help us only, when we wish to write music ourselves - and want to understand what can be done - or when we transcribe to another instrument on which we add or leave out notes, which of course has to be done with an understanding of the harmony (although our ear and a good taste might replace to a good deal the formal analysis).

This is different with hidden and open scales.

A scale has a clear directio., Except in rare cases, a scale ascending points to a crescendo, a scale descending to a diminuendo.

Discovering hidden scales gives the shaping of dynamics a larger scale:

We must play the notes belonging to a hidden scale in a way that the listener can follow the existence of the scale, point these notes out - strong or subtle.

This gives suddenly the piece a formal structure, through which a good player acts as a tour guide to the listener.

The performer explains the composition withoutb using words - explains the structure by simply playing the underlying structure.

Of course it adds clarity and beauty to a performance.

In particular this means:Already during the first 6 bars, after the descending scale in bar 1 has been stated, the rising dynamic of the first notes of the bar indicate a crescendo to bar 6 - we arrive at least in poco forte.

From bar 7 to 13/14 the "hidden scale" leads us from the tonic "C" note by note down to a "G" in 2 bar segments, which in itself include twice a descending transition during the last 4/16.

We have no other option than to arrive in bar 13 in piano.

In the following bars I indicated all first notes of a bar, which I hear inside me as a guide, when I play, as if following Bach's instruction.

A larger development begins in bar 33: firstly in bars, then in a distance of beats, the "hidden scale" descends down more than one octave and finally drops to the lowest note of the cello, the open C.

As it is often the case, from here on (bar 37) a two bar sequence rises and we could attach our marks virtually to nearly any note within the sequence - we can here the rise in many related notes.

I circled the first note of the 2 bar units, but of course I could have circled the highest or lowest note as well: we can hear the hidden scale in many related notes.

From bar 50 to 56 we find two bar units, which have a nice melody in itself.

Each unit is like a large step decorated with a mosaic and diplays within each of the 2 bars step a melody (always the changing note), which when played out adds a brilliance to the passage.

Each step descends up to the F and rises over the F# to the G, adding some weight to the end of the passage in bar 66.

The ending (from bar 71 on) starts in a C scale like in bar 2, like a recapitulation.

More gradual and stricter than in the beginning the "hidden scale" leads us in a crecendo up, again like at the start to the E.

But fro her the dynamic tumbles down to a piano:

From bar 77 to 78 the outer parts open up like a crescendo sign, and so do again from bar 79 to 81: if we connect with a pen the outer notes, the graphic lines describe a crescendo.

Once arrived here, the outer notes stay - as if finally having arrived - indicating a constant strong sound towards the end.

As mentioned in the chapter on structure, the dramatic effect relies on the rests (there is no rest in this movement before the 10th last bar), which makes one think, that the piece has maybe been written for a larger hall, where the silence of the rests is filled with the diminishing echo.

Interestingly enough - and to foster this idea - the last chord is only 1/4 with written out rests: finishing quite swiftly and wait for the sound to vanish until the piece has really ended.

Dynamic Mapping: Hidden and open Scales in (indicated in red). [print: Doerffel 1879]

If played well, the listener can easily follow the indicated "hidden scales".I included on this page a general guide on "dynamic mapping".

This "map" gives us the dynamic instruction, which in later times has been written out by the composer, like forte and piano.

But in Baroque times this was not common - and to some part the understanding of the structure - usually polyphonic - effects the interpreation in a way, that can't be described by an overall dynamic as the different simulaneous parts have different dynamics and like here, single notes are important to "point out" in a careful way, which can't be simple labelled with a dynamic.

The interested reader or player can read more on this by clicking here on: Dynamic Mapping & Phrasing (click here)Dynamics

Very rarely I write specific dynamics in.

The performance, if private or public, depends very much on the mood of the day, the nature of the performance space and the audience.

This is particularly true for the Preludes, the more atmospheric introductory movements.

The dance movements should vary in the repeats.

Defined dynamics lead to play just what is written without understanding and having a sensitivity to the situation.

I find, too many "readers" (particularly players, who don't play by memory) find in written dynamics a way to play a piece like a study, with little feeling and little understanding.

I try with my articles and graphps as much as I can to get away from just copying what is written, but understanding and experiencing - living - the music every time anew we play it.

Also, the historically later developed way of writing dynamics in relies on, that all parts have for a worthwhile period the same dynamic.

In Baroque interpreation the dynamic line is much more complex as to simply write an overall average dynamic in (which might be a reason that composers didn't become convinced it might be advisable to write "a dynamic" in).

A good interpreation distinguishes the different dynamics of beat 1 and 2, of bass and top melody, of so many factors, that writing it in is either too complicated or fails the purpose -

and as mentioned, in repeats we should vary, on different days and in locations we should play differently - intergrated with time and space.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

For my arrangements & compositions for cello, 2 cellos, cello & guitar on sheetmusicplus click on icon

Overview of the harmonic structure of the dance-movementsThe dance movements of all 6 suites are remarkably similar in structure, all 36 dance movements havein fact the same structure, from the shortest to the longest one :

All dance movements are written in two parts and each part is repeated.

In contrast a - and as strict - no Prelude includes a repeat.

This is intersting as in the Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin these elements vary.

I will give here an overview of the harmonic structure, which is - as with all Baroque composers - fairly uniform, but in fact not always.

I note here the harmonies of the beginning and end of each part.

In this sketch I indicate the sections framed by repeat marks; I indicate the keys and in brackets the functions.

In most movements the upbeats are in the same key as the first full bar (or full bar after the repeats) in others they may indicate a Dominant character.

In this sketch I refer always to the first full bar with the exception of the Gavottes.

In the Gavottes the starting chord - or note - on the 3rd beat has the strength and impact of the real beginning, carrying usually the Tonic harmony.

In the other movements I made a note when the beats has a Dominant character {upbeats in Dominant character}.Abbrevations:

(T) = Tonic / (S) = Subdominant (D) = Dominant

(Rmaj) = Relative major / (minD) Minor DominantSuite No 1 - G major (Menuet II in G minor)

Allemande ||: G (T) - D (D) :||: D (D) - G (T) :||

Courante ||: G (T) - D (D) :||: D (D) - G (T) :||

Sarabande ||: G (T) - D (D) :||: D (D) - G (T) :||

Menuet I ||: G (T) - D (D) :||: D (D) - G (T) :||

Menuet II ||: G (T) - D (D) :||: D (D) - G (T) :||

Gigue ||: G (T) - D (D) :||: D (D) - G (T) :||Suite No 2 - D minor (Menuet II in D major)

Allemande ||: Dm (T) - A (D) :||: A (D) - Dm (T) :|| {upbeats in Dominant character}

Courante ||: Dm (T) - A (D) :||: A (D) - Dm (T) :||

Sarabande||: Dm (T) - F (Rmaj) :||: F (Rmaj) - Dm (T) :||

Menuet I ||: Dm (T) - A (D) :||: A (D) - Dm (T) :||

Menuet II ||: D (T) - A (D) :||: A (D) - D (T) :||

Gigue ||: Dm (T) - A (D) :||: F (Rmaj) - Dm (T) :||Suite No 3 - C major (Bourree II in C minor)

Allemande ||: C (T) - G (D) :||: G (D) - C (T) :|| {upbeats in Dominant character}

Courante ||: C (T) - G (D) :||: G (D) - C (T) :||

Sarabande||: C (T) - G (D) :||: G (D) - C (T) :||

Bourree I ||: C (T) - G (D) :||: G (D) - C (T) :||

Bourree II ||: Cm (T) - Eb (Rmaj) :||: Eb (Rmaj) - C (T) :||

Gigue ||: C (T) - G (D) :||: G (D) - C (T) :||Suite No 4 - Eb major (Bourree II in Eb major)

Allemande ||: Eb (T) - Bb (D) :||: Bb (D) - Eb (T) :|| {upbeats in Dominant character}

Courante ||: Eb (T) - Bb (D) :||: Bb (D) - Eb (T) :||

Sarabande||: Eb (T) - Bb (D) :||: Bb (D) - Eb (T) :||

Bourree I ||: Eb (T) - Bb (D) :||: Bb (D) - Eb (T) :||

Bourree II ||: Ab (S) - Eb (T) :||: Ab (S) - Eb (T) :|| {upbeats in Dominant character, here Eb (original T) as D to S}

Gigue ||: Eb (T) - Bb (D) :||: Bb (D) - Eb (T) :||Suite No 5 - C minor (Gavotte II in C minor)

Allemande ||: Cm (T) - G (D) :||: G (D) - Cm (T) :||

Courante ||: Cm (T) - G (D) :||: G (D) - Cm (T) :|||

Sarabande||: Cm (T) - Eb (Rmaj) :||: Eb (Rmaj) - Cm (T) :||

Gavotte I ||: Cm (T) - G (D) :||: Gm (minD) - Cm (T) :|| {indicated harmonies starting on the 3rd beat} *

Gavotte II ||: Cm (T) - Cm (T) :||: Eb (Rmaj) - Cm (T) :|| {indicated harmonies starting on the 3rd beat} *

Gigue ||: C (T) - Eb (Rmaj) :||: Eb (Rmaj) - C (T) :||Suite No 6 - D major (Gavotte II in D major)

Allemande ||: D (T) - A (D) :||: A (D) - D (T) :||

Courante ||: D (T) - A (D) :||: A (D) - D (T) :||

Sarabande||: D (T) - A (D) :||: A (D) - D (T) :||

Gavotte I ||: D (T) - A (D) :||: A (D) - D (T) :|| {indicated harmonies starting on the 3rd beat} *

Gavotte II ||: D (T) - D (T) :||: D (T) - D (T) :|| {indicated harmonies starting on the 3rd beat} *

Gigue ||: D (T) - A (D) :||: A (D) - D (T) :|| {upbeats in Dominant character}* The Gavotte's have an interesting harmonic layout, which is unusual, perhaps "cavort" (the words "Gavotte" and "cavort" are synonymous in their origin).

I couldn't find general information on the harmonic subject, but it seems, Bach put by purpose things in a "cavort" manner:

The carrying harmony is set unlike all other movements not on beat ONE, but on the Third beat.

The second half of Gavotte I, Suite 5, starts with a G minor Dominant chord, going towards the major Tonic in a piece, where the tonic is C minor.

It seems to me as if Bach put like in the Cantatas meaning into the chords: "cavort" is expressed by turning the modes of major and minor back to front,

beat One is swapped with beat Three - the crazy dance, where rules are offended in a masterly way.

BACH PROJECT DONATION

If you wish to support the Bach Cello Suites research, you can do so.

New videos, research are now first published on my patreon forum.

A donation will entitle you to have access and be notified of new videos

on the Bach Cello Suites - research, recordings, talks,

lessons to the movements and make you a member of the cello course

including the CELLO ISSUES series.

To have a look, click below, go to "Collections":

https://www.patreon.com/c/georgcello/

The PRELUDE

The Prelude is an introduction to the following dance movements of the Suite.

Literally translated pre-lude means a "fore-play", the part before the real thing starts.

In general it introduces the key and sets the character for the Suite.

From the composers and the performers view it is the least restricted movement; it does not need to follow a certain pattern or rhythm like the dances, it is freer.

For me the Preludes are often the strongest piece in the Suites, each is very powerful, with a strong impact.

They can stand alone as a performance item.Historically the Prelude had often been improvised even during Bach's early years; the performer made the Prelude up on the spot.

As a composition it was frequently written without bar lines as e.g. in Preludes of Bach's friend Weiss (who was regarded the finest - and highest paid - lutenist of the century).Bach's Preludes to the Suites should convey an air of freedom, "quasi improvisando" as Dvorak would say.

It would certainly be a misunderstanding to play a Prelude regular like to a metronome.

The difference to the strictness of the following dances should remain noticeable.Structurally the Preludes in the major keys consist basically of triads and scales, introducing the key of the Suite.

Suite 1 and 4 have a distinct separation into 2 parts, returning at the end to the starting theme, a feature shared with the other major Preludes.

Prelude 1 and 3 share an impressive section in the 3rd quarter resting on on the Dominant note played with an open string and wandering melodies / chords upon this pedal point.

The Preludes in the minor keys display a much more melodious character.