Return to the Homepage of Georg Mertens

Violinist Gustaw Szelski

1950 - 2021

&

The Jenolan Caves Concerts

Youtube channel -

Solos, Duos,

The 6 Bach Cello Suites

Cello Issues

Poems by

Georg MertensPoems by Han Shan

(Cold Mountain)

edited

by Georg Mertens

- Japanese

- Chinese

- Korean

- Hindi

- i - Russian

- i - Turkish

- Greek

- Espanol

- French

- Italian

- Polski

- Hungarian

- Portuguese

- // - Arabic - //

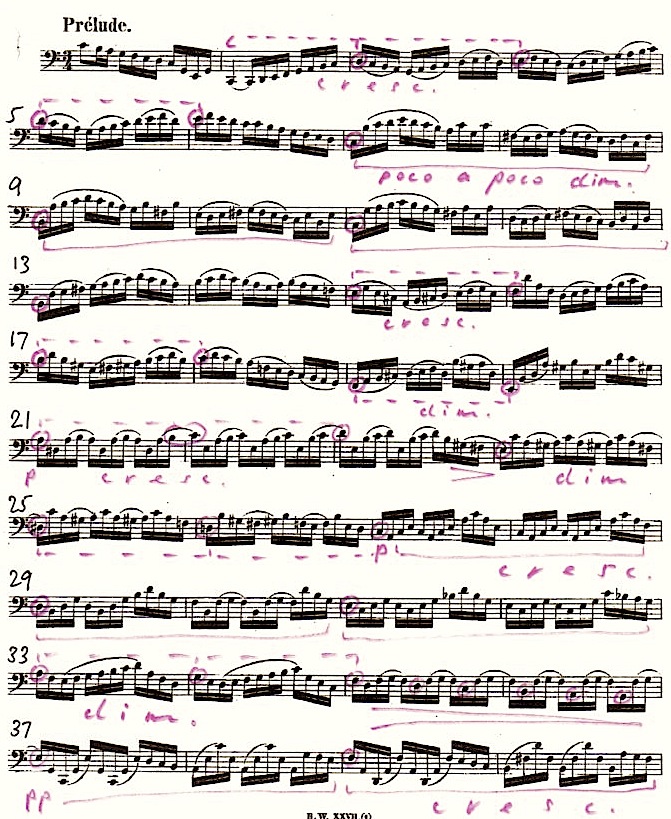

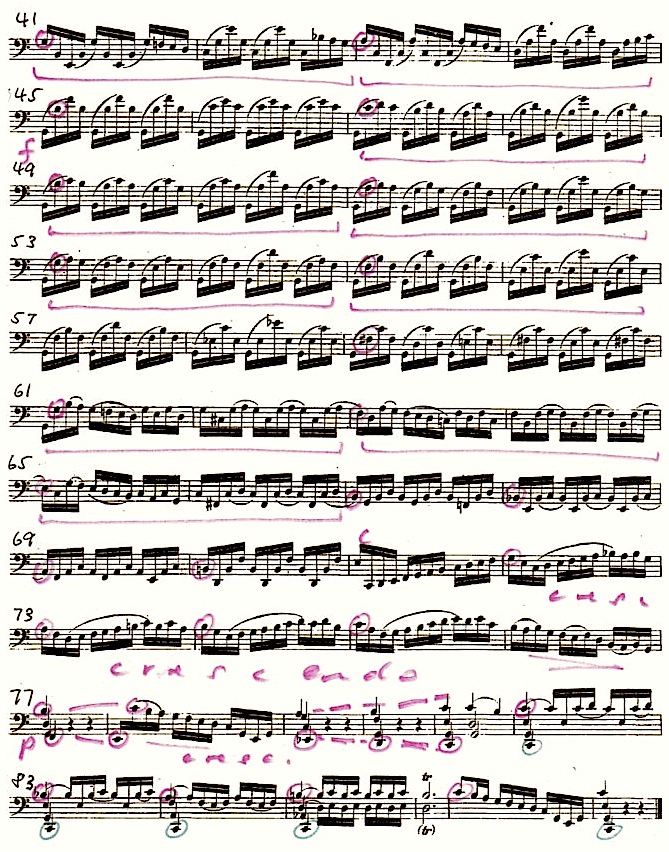

The Six Suites for cello solo by Johann Sebastian Bach

History - Analysis - Detailed Interpretation - Audio - Video

The most comprehensive site on the Bach Cello Suites.

Copyright for this webpage by Georg Mertens

(c) 2012 Katoomba / Australia

Published on Bach's date of Birth 21st March (2012).Quotation and references to original and new thoughts or material from this site needs to state the author of this website.

Any use of material of this site, which can make profit is only permitted after arrangement with the author.

Contact:

email: georgcello@hotmail.com

CONTENTS:

THE EDITIONS OF THE 6 CELLO SUITES IN HISTORICAL ORDER

- 85 Editions from 1726 to 2000 (click here)FIRST EDITIONS OF THE CELLO SUITES for OTHER INSTRUMENTS (click here)

Considerations

The oldest manuscript by Kellner

The manuscript by Anna Magdalena Bach - Was Anna Magdalena the writer of the Suites?

Manuscript C - Manuscript D

Lost ManuscriptsThe "Loure" in Cotelle's first print

Dotzauer's first print

Groups of Print Editions

A "Landmarks" comparison of the early Sources

A possible (different) Genesis of the Suites

ConclusionThe task of INTERPRETING the SIX SUITES

Interpreting - A practical comment - Playing by Memory - Written Dynamics (click here)Follow "Simile" -

Baroque or modern Bow

Notes & Slurs in the manuscripts

Slur-shifts - Slurs or Phrases

Phrasing in Song - Instrumental PhrasingDynamic Mapping & Phrasing (click here)

Dynamic Mapping

The Implied Dynamics in the Melodic Line

"Hidden Scales"

The macro-dynamic Guide (click here)

Step Dynamic

Polyphony, Counterpoint

Melody & Accompaniment

Repetitions & Echoes

Rhythmical Dynamics

The micro-dynamic Guide (click here)

Baroque Style

Vibrato

Structure & the new Romanticism in Baroque Dress.Harmonic Analysis (click here for a harmonic Analysis of Prelude 1 & 3 [linked web page])

THE SUITE and its MOVEMENTS - History & Characteristics (click here)

Prelude - (click on movement to forward)

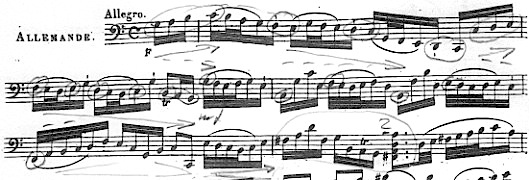

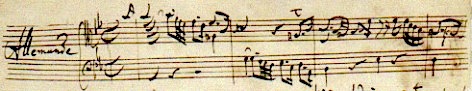

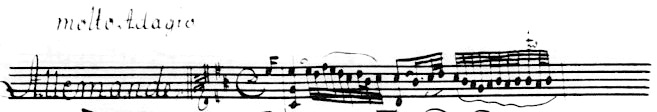

Allemande -

Courante -

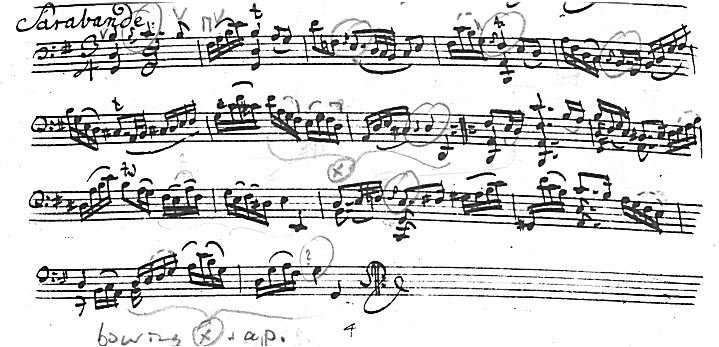

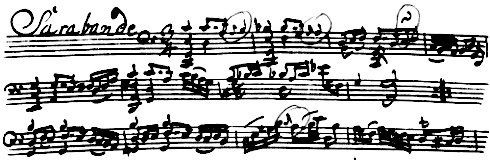

Sarabande -

Menuet -

Bourree -

Gavotte -

Gigue (click on movement to forward)General overview of the harmonic structure of the dance-movements (click here)

INTERPRETATION in DETAIL:

Suite V (click here)

- Including: The hitherto unknown "B - A - C - H" citation in 4 movements of the 5th Cello Suite

To the surname "Bach" (click here)The Bach Cello Suites during my life (click here)

(for private online cello lessons see bottom of this section)

AUDIO - CD's - Downloads: click here

__________________________________________________

THE EDITIONS OF THE 6 CELLO SUITES

(IN HISTORICAL ORDER)c 1720 - 1726 The estimated year Bach wrote or started writing the 6 Suites for cello solo. The original has been lost.

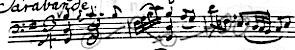

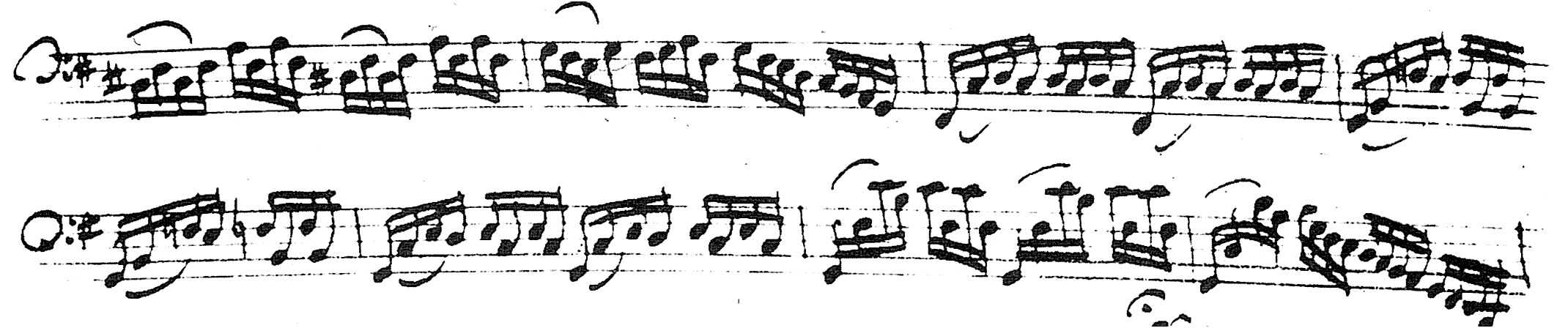

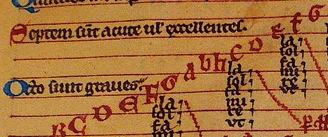

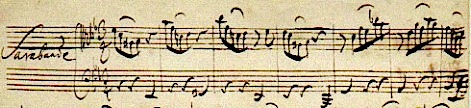

c 1726 - manuscript by Johann Kellner

Title: Sechs Suonaten pour la Viola de BassoKellner was a friend of Bach, a flautist and organist.

Therefore his bowings give rather a sense of phrasing and are inconclusive when used as bowing instructions.

Suite 5 is written in this manuscript for standard tuning, which hints to an existing edition in standard tuning, because we can't assume, that another person than a cellist would be able to understand the jump at the correct notes considering position play.

Also, he did not finish Suite 5. He started for a few bars the Sarabande, stopped and left out the Gigue altogether. I assume Kellner noticed, that the he had seen the Sarabande and Gigue before, which Bach also used for the flute suites.

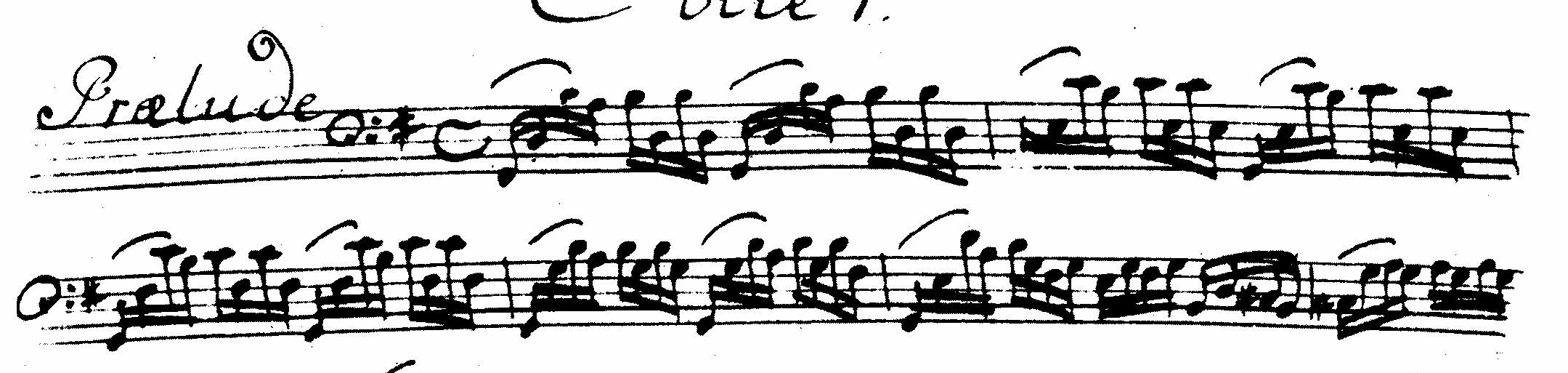

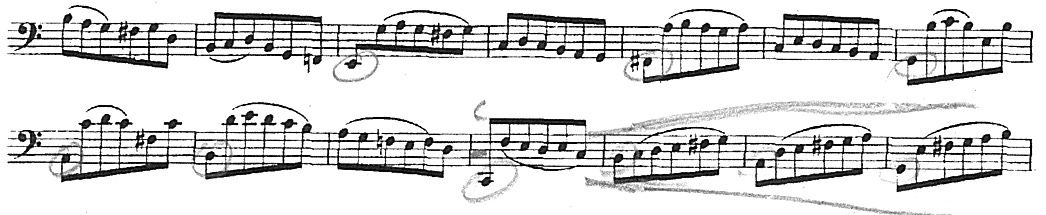

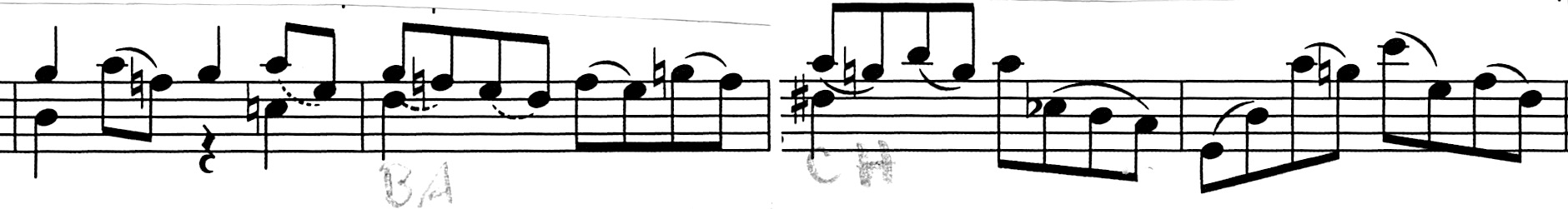

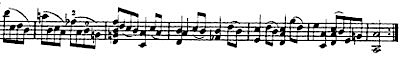

c 1727 - 31 manuscript by Anna Magdalena Bach

Title: Suites a violoncello senza bassoAnna Magdalena's manuscript is regarded as possibly the closest to the original, obviously because she must have copied it from the original.

Certainly regarding the notes her copy must be the closest to the original.

Unfortunately she was not familiar of the inner logic of a string players' bow technique.

As demonstrated by her copies of the violin Sonatas & Partitas - where we have Bach's original - she miscopied frequently whole passages of bowings.

We have not to forget, that Anna Magdalena did the copying in her "spare time", which means, after she had managed to put a part of Bach's 20 children to bed.

By playing from her copy we need to move away from taking slur by slur literally, we must rather try to understand the messages of phrasing and bowings coming through in examples within the movement. Then we need to extend these patterns undisturbed by contradictions.

Naturally it remains very difficult to interpret what is meant - and what is not meant.

Also, Anna Magdalena's copy looks already back on a certain time span of experience with musicians having played the Suites.

Especially in the Prelude of Suite 1 we can discover a conscious moving away from the standard bowing of 3 slurred to a more complex pattern.

This complex pattern works as written. Therefore I assume, J.S. Bach must have supervised the copying and instructed her to change the bowing due to him not being happy with the sound of the "original" bowing, after he had heard several cellists play his original version (see also: comment to Prelude No 1).

Maybe her bowing of Prelude 1 can be seen as a second original draft of Bach.

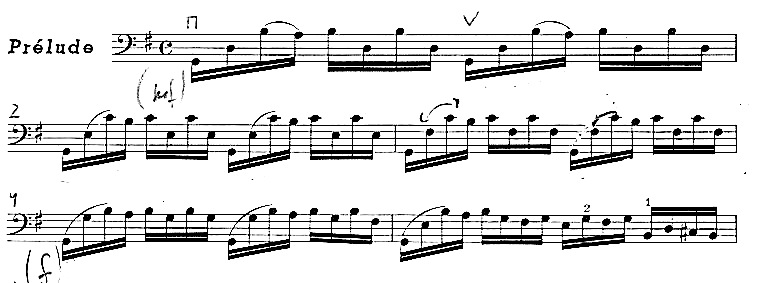

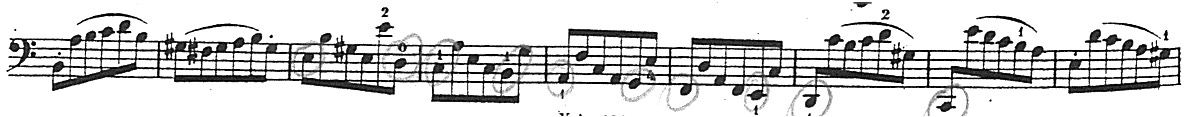

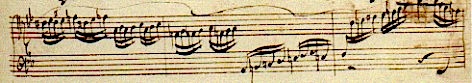

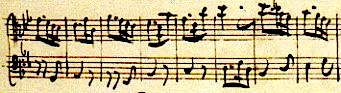

1750 - 1800 - manuscript called 'C', author unknown

Title: Suiten und Preluden fur das VioloncelloThis is the first copy of a cellist. We can play through this copy and it all makes sense - if we share the interpretation or not.

This copier lived historically already not anymore in the Baroque period, in which performers added ornaments according to their taste or to tradition.

In his manuscript the editor included the ornaments, which were traditionally played and regarded as being correct and belonging to a stylish performance.

He must have felt that performers of his time would leave out the proper ornaments, when he wouldn't write them in.

Therefore this copy gives us an important inside of Baroque performance. We can compare Anna Magdalena's copy without the ornaments and seeing in his copy, where they would have been played already in her time, although they were not written in.

This is especially so in the Sarabandes.

1775 - 1800 - manuscript called 'D', author unknown

Title: 6 Suite a Violoncello SoloThis copy is similar like manuscript "C" but less clear.

However this edition is clerly written by a cellist. When playing it through the bowings work out and it sounds interesting.

The version is less strict and seems to include the ideas in bowing and phrasing form the other manuscripts.

I actually like playing it - although the lines are so thin one must nearly know the work by memory.

As in manuscript "C" ornaments are noted.

here is a recording of manuscripts "D"

The four manuscripts above are the only known sources from before 1800 and are commonly taken as the closest to the lost original by J.S.Bach (see also "CONCLUSION").

They have been published by Baerenreiter and also by the Petrucci Library.

c 1720 to c 1850 ? - Many lost manuscripts (used as a base for the early prints)The 4 surviving manuscripts mentioned above had not be used by any cellists of the time.

The books were too thick to fit on a music stand. There are also no fingerings in nor any signs, that they have been used.

That is why they have survived in excellent condition without any wear and tear.

Cellists must have used first the lost manuscripts plus hand copies of these and used later the prints after enough different prints reflecting all kinds of interpretations had been printed (see CONCLUSION for more details).

____________________________________________

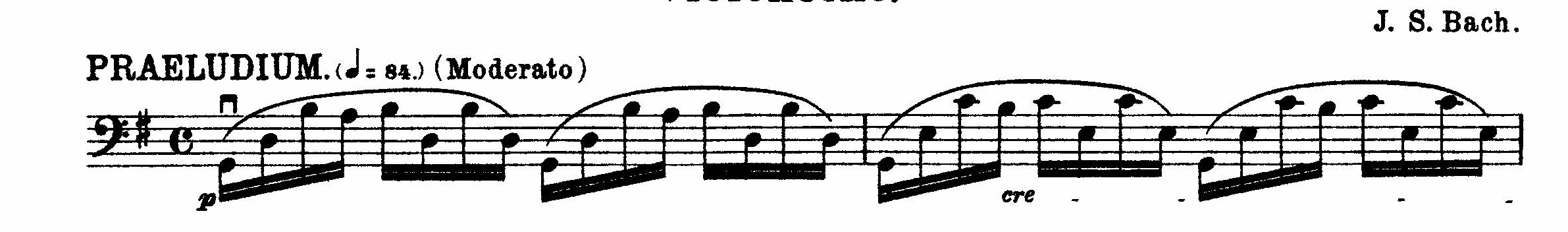

c 1824/5 - Editor unknown (probably M. Norblin), publisher:

1 - Janet de Cotelle, Paris 1824

2 - H.A. Probst, Leipzig 1825

Title: Six Sonatas ou Etudes pour le Violoncelle SoloOften called 'the first printed edition'.

To call this edition the first is not a secure fact, but rather an assumption and also a dedication - a kind of Romanticism - to the story, that the great cellist Pablo Casals found this edition in a second hand shop and was later responsible for making the Suites known to a wider audience outside Germany.The Baerenreiter Urtext Edition includes a copy of this publication. In a way this is unfortunate.

The edition lacks cooperation between editor and publisher;

it is impossible to play the movements through as they are.

Every few lines one gets stuck in the wrong bow direction.

Obviously the publisher had no idea of the inner logic of bowings, which are different than phrasing.

it is said Norblin just gave his manuscript to the editor, but had immediately go on tour.

Consequently he was not around to proove read. Even some movement titles are wrong.(in comparison to the next edition:)

Simultaneously Dotzauer edited his first edition (see below).

Dotzauer learnt composition from Ruettinger, who was a student of Kittel, a Bach student.

He certainly had access to direct information and understanding, had several manuscripts to choose from, as he lived in the same town as Bach and was only two removes from Bach as a composition student.Also, he must have kept an eye on the whole production as we can play through the Suites and it all makes sense from a players point of view.

I wish Baerenreiter would have published this edition as it would be by far the more interesting one.

It also points clearly to further manuscripts, which have been lost and are different to the four known ones.

I got hold of the Prelude of Suite I from the 1826 edition thanks to the kindness of the still existing original editor Breitkopf (Breitkopf's edition is same edition as the prior Probst, which was virtually simultaniously published as Cotelle's edition).

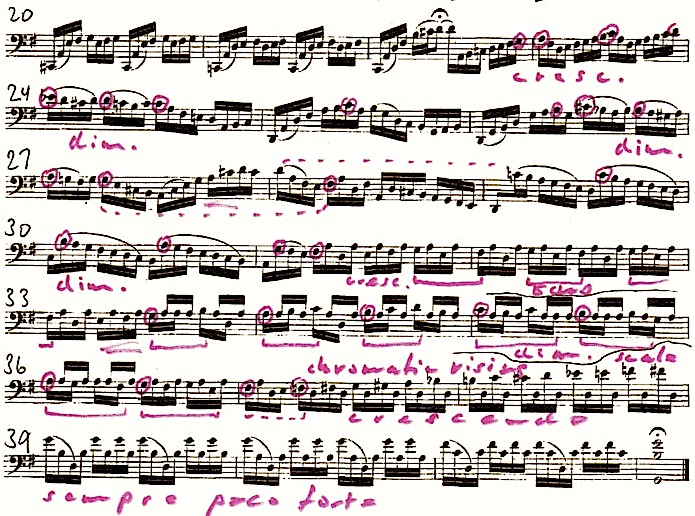

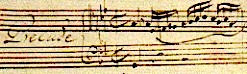

c 1825 - Friedrich Dotzauer, Leipzig

Title: Sechs Sonaten (see comment above)&

1826 - Breitkopf, Leipzig

1831 - Kistner, Leipzig

1890 - Breitkopf, Leipzig

1896 - Breitkopf, Leipzig

&

1916 - Guiseppe Magrini - Dotzauer, publisher: Ricordi, Milan

1956 - Walter Schulz - Dotzauer, new Ed. publisher: Pro Musica, LeipzigThe Dotzauer Edition had been published for a remarkable period of over 130 years.

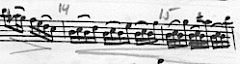

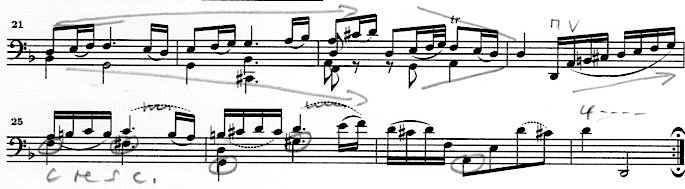

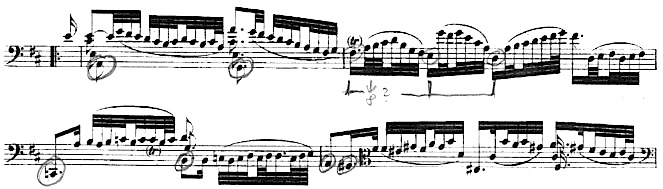

The 1st edition has 2 bowing misprints on page 1, in the bars 10 and 28, which are corrected in later editions (I marked the corrections underneath).

However, because of the insecurity of having no original, Dotzauer consistently printed certain wrong notes, which we know today were in fact wrong (I have not seen the 1916 & 1956 editions).

They appear in the bars 22 / 24 / 26 & 27 (I circled them).

Cotelle prints the same mistakes in bars 22 and 26.

1827 - Richter, Petersburg1866 - Friedrich Gruetzmacher, publisher: Peters, Leipzig

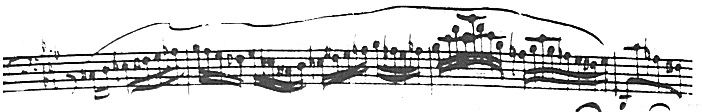

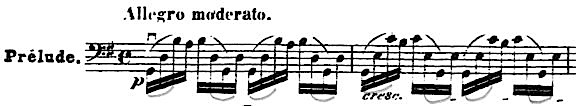

Title: Six Sonatas ou Suites pour Violoncelle seulSuite 1 increased slurring in the Prelude

Suite 6 transposed to G major

& c 1885 - Friedrich Gruetzmacher 'Concert Version', Peters, Leipzig

c 1900 - Concert Version 2nd Ed. Peters, Leipzig1879 - Alfred Doerffel (Bach Gesellschaft), publisher: Breitkopf, Leipzig

1888 - Alwin Schroeder, publisher: Kistner, Leipzig

1897 - Norbert Salter, publisher: Simrock, Berlin

1898 - Robert Hausmann, publisher: Steingraeber, Leipzig

&

1935 - Hausmann revised by Walter Schulz, Steingraeber, LeipzigTo my knowledge the first edition with B natural in bar 26 of Prelude 1 - corrected by the owner of the copy back to Bb!

1900 - Julius Loeb, publisher: Constallat, Paris

&

1923 - Loeb new Ed., Constallat, Paris1900 - Julius Klengel, publisher: Breitkopf, Leipzig

&

1953 - Julius Klengel, new print, Breitkopf, Leipzig

** NOTE: Of the 16 editions from 1824 to 1900 , 12 had been published in Leipzig and only 4 in other cities!1907 - Jacques van Lier, publisher: Universal Edition, Wien

1907 - Wilhelm Jeral, publisher: Universal Edition, Wien

1911 - Hugo Becker, publisher: Peters, Leipzig

Title: Sechs Suiten (Sonaten) fuer Violoncello solo

&

1946 - reprint with publisher: IMC, New York

1953 - reprint, Peters, Leipzig

&

19 ? - reprint, Peters, New York (my edition)To my knowledge the Becker edition is the first, which put forward the bowing of starting with 8 notes slurred in Prelude 1 - today the most played version.

My edition (bought in Australia, no year to be found, (printblock No 9148) has still the title in the inside cover : Sechs Suiten (Sonaten) fuer Violoncello solo

Prelude G , p 1 - still available

1914 - Evgueni Maigren, publisher: Jurgenson, Moscow

1918 - Fernand Pollain, publisher: Durand, Paris

1918 - Joseph Malkin, publisher: Fischer, New York - Very similar to Hugo Becker, little changes, same ideas.

1919 - Percy Such, publisher: Augener, London (1st UK)

1920 - Cornelius Liegeois, publisher: Lemoine, Paris

1920 - Paul Bazelaire, publisher: Max Eschig, Paris

&

1933 - 2nd rev. Ed. Max Eschig, Paris1921 - Paul Kurth, publisher: Drei Masken, Wien

1923 - Luigi Forino, publisher: Ricordi, Milan

1928 - Wilhelm Jeral, publisher: Muztorg, Moscow

1929 - Diran Alexanian, publisher: Salabert, Paris

Includes for the first time the facsimile manuscript by Anna Magdalena Bach.

This edition is the first sample of writing the music out including an intellectual analysis, which should introduce the player to phrasing and an understanding of Bach's polyphony in the solo part.

Later Mainardi and Tortellier followed this idea.

Alexanian's attempt is unfortuately so confusing that is is nearly impossible to read fluently.

1939 - Frits Gaillard, publisher: Schirmer, New York1941 - Enrico Mainardi, publisher: Schott, Mainz

&

1966 - Mainardi, new rev. Ed., Schott, Mainz

This is the first edition I was given when I was 12. Mainardi used a layout differentiating the top / middle and bottom voices. Before I knew the words counterpoint and polyphony I tried already to do justice to the clarity of parts according to this edition.

Mainardi's idea is following Alexanian, but is clearer.

Like Alexanian he puts his own ideas first disregarding the bowings of the manuscripts.1944 - Paul Gruemmer, publisher: Doblinger, Wien

This edition includes the facsimile manuscript of Anna Magdalena.

In difference to other editions (like later Kurtz) Gruemmer gives a faithful modern print of Anna Magdalena's bowings next to the manuscript.

The print is one of the clearest available and is one of the few if not the only one, where the editor puts his own view in the background and gives account of the manuscript in a modern note setting.

This edition could be one of the very best for the advanced palayer would it not unfortunately have so many printing mistakes (not historically doubtful notes, but real mistakes).

1947 - Semon Kosolupov, publisher: Muzgiz, Moscow1950 - Bach Gesellschaft Edition, reprint, publisher: Lea Pocket Score, New York

&

1988 - Bach Gesellschaft, Dover, New York

1950 - August Wenzinger, publisher: Baerenreiter, Basel

In my student time everyone played this edition. The print is good. It claims to be Urtext (original or the closest to) but it is indeed a personal edition and mix of the editors way of playing without any explanation why a choice has been made.1953 - J. Ebner, publisher: Hug, Zuerich

1954 - Gino Franzesconi, publisher: Suvini, Milan

1957 - Alexander Stogorsky, publisher: Muzgiz, Moscow

Includes facsimile manuscript of Anna Magdalena

1957 - Richard Sturzenegger, Suites 4-6 only, publisher: Reinhardt, Munich / Basel

1958 - Kazimierz Wilkomirski, publisher: PVVM, Crakow

&

1962 - Wilkomirski, publisher: PVVM, Crakow

1964 - Wilkomirski, publisher: PVVM, Crakow

1967 - Wilkomirski, publisher: PVVM, Crakow

&

1972 - Wilkomirski, new rev Ed., publisher: PVVM, Crakow1963 - Lieff & Marie Rosanoff, publisher: Galaxy, New York

1964 - Dimitry Markevitch, publisher: Presser, Bryn

&

1985 - Markevitch, 2nd rev Ed., Presser, Bryn1965 - Paul Rubart, publisher: Peters, Leipzig

1966 - Paul Tortellier, publisher: Augener, London

&

1983 - new ED., publisher: Stainer, London

1968 - Giuseppe Selmi, publisher: Carisch, Milan

1970 - Daniel Vandersall, publisher: Vandersall, NJ

This edition is just the notes without bowing, leaving it up to the player to write bowings in - thus saving the mess of crossing out what is suggested.

This is the opposite to the approach of writing too much (Tortellier / Mainardi / Alexanian)1971 - Janos Starker, publisher: Southern, NewYork

& Peer International Corporation, New York, Hamburg1972 - Pierre Fournier, publisher: IMV, NewYork

1974 - Eugen Eicher, publisher: Volkwein, Pittsburg1978 - George Pratt, publisher: Stainer, London

1981 - Jaqueline Du Pre, publisher: Hansen, Copenhagen

1982 - Maurice Gendron, publisher: Zen-On, Tokyo

1984 - Marcel Bitsch / Klaus Heitz, publisher: Leduc, Paris

1984 - Edmund Kurtz, publisher: IMC, New York

Includes the facsimile manuscript of Anna Magdalena (a very good copy).

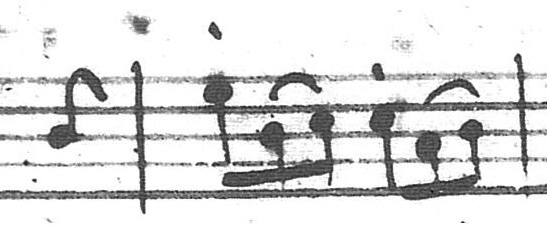

For me this is a strange edition. On one side you have the manuscript - as you would think to show an original - on the opposite side the music in print, bowings totally unrelated, as if the facsimile has been added because it looks nice... [Exception, in Minuet I of Suite 1, Kurtz made a strange choice: Anna Magdalena forgot to draw the leggier line for the "E" in the 3rd last bar. Kurtz decided to interpret the note as a "D" - to me it seems like a stubborn individualism (as if nobody else noticed, that the line is missing!)

But, in fact the head is in the correct E space in distinction with the lower head of the D after and everyone concluded that it counts more than counting lines. Unfortunately e.g. Rostropovich plays the misfitting "D" probably due to respect to the cellist.]

The print is also unfortunately beneath standard, lines are too close together, notes are disappearing in the fold, some not even printed.( please see Minuet 1 of Suite I ( Kurtz misinterpretation of the note "E") and in "Sarabandes" his after my opinion wrong guide to the interpretation of double stops)

1985 - Bruno Vitale, publisher: Curci, Milan

1986 - Pablo Casals (Madeleine Foley / D. Soyer / Ann Arbor), publisher: Continental

1986 - A. Vlassov, publisher: Muzgiz, Moscow1987 - Giambattista Valdetarro, publisher: Zanibon, Padova

1988 - Neue Bach Ausgabe (Ed. Hans Epstein), publisher: Baerenreiter, Kassel

&

1995 - Neue Ausgabe Volume VI / 2, Epstein, BaerenreiterThis was the first edition showing a facsimile of the first four manuscripts.

The print was very small, the quality like average shiny photocopies of the 70th and the price astronomical. I paid in 1996 $185 for the pocket size edition booklet.

It should be said, that the Alexanian edition printed the facsimile of Anna Magadalena in 1929 in a far superior reprint; the technical possibilities were certainly there to do a better job.

(The volume with comments was so overpriced, I never met anyone who bothered purchasing it).&

2000 - Bettina Schwemer / Douglas Woodfull-Harris: publisher: Baerenreiter, KasselThis time Baerenreiter had the great idea to edit the 4 facsimiles in separate volumes, making comparing easy. Also, the quality of prints is as good as can be and the price is reasonable.

Unfortunately - as mentioned above - Baerenreiter choose the French first print above the German Dotzauer one. The French one time off edition was obviously quickly published without correction by the editing cellist - making it an uninteresting edition, too casual edited to propose virtually any view at all - where as the Dotzauer edition was of such a convincing quality, that it had been reprinted for 131 years.

The Baerenreiter edition includes also a very insightful collection of guide lines on performing during Bach's own time by e.g. Leopold Mozart, Quantz and Geminiani.

I personally come to different conclusions than the editors about interpretation and history - which I think doesn't matter - as probably many cellists will make their own conclusion with all the invaluable information given readily translated.The extra text volume alone makes the purchase of this wonderful package worthwhile.

_______________________________________

1988 to today - There are the following editions available to today of which I was not able to find the year of publication:

Thomas Mifune. publisher: Edition Kunzelmann

Egon Voss. publisher: Henle Urtext. Wien

_______________________________________

After the appearance of the Internet many new editions appeared on the net.

I like to mention just one, the edition by Werner Icking.

Not only because it is the first edition where I found movements, in which I didn't need to correct one single bowing: his thoughts seemed to reflect mine! (This had never happened before).Like me, Icking studied the Sonatas and Partitas for violin solo in comparison to the cello suites instead of relying on only the facsimiles.

One of the main features of Bach's bowings is: they are simple and consistent.

Bach is not a composer who wishes to express a phrase with a bow technique. He writes in passages, the interpretation should come rather from our ability to phrase without the aid of complicated bowings.1997 - Werner Icking, publisher: Werner Icking Music Archive (WIMA), Siegburg

______________________________________________________________________

EDITIONS OF THE CELLO SUITES FOR OTHER INSTRUMENTS

I attempted here to find the earliest editions, who influenced later ones.

Again, today many editions are available on line undistinguished from very good to quite bad.

EDITIONS for VIOLA

c 1880 - Stade, Heinze, Leipzig

1916 - Louis Scecenski, Schirmer, New York

c 1930 - Suite 1-4, Herrmann Ritter, F.Hofmeister, Leipzig

1944 - Samuel Lischey, Schirmer. New York

1951 - Watson Forbes, Chester Music, London

My father had this edition. The first Bach I played was my own transcription of Prelude 1 transposed from this edition, when I was 11.

1953 - Fritz Spindler, F.Hofmeister, Leipzig

1962 - Fritz Spindler, Muzgiz, Moscow

There exist also a Russian edition, which I have been told is lterally the Spindler edition. In this edition from 1962 the heading of Prelude 1 reads: "SONATA" I !!

1962 - Robert Boulay, Leduc, Paris

1982 - Milton Katims, IMC, New York

EDITIONS for VIOLIN

c 1860 - David, Breitkopf, Leipzig

EDITIONS for DOUBLE BASS

1885 - ? Schmidt, Boston

EDITIONS for PIANO

1870 - Raff, Pieter/Biedermann, Leipzig/Winterthur

? - F Gruetzmacher, 6 pieces from the Suites op 71, ?

1924 - L.Godowsky, Carl Fischer, New York

1931 - Siloti, Carl Fischer, New York

EDITIONS for CELLO & PIANO

1985 (posth) - Robert Schumann, Suite 3, Breitkopf. Wiesbaden (disappointingly not published to today)

1864 - W von Stade, 6 Suites, Heinze, Leipzig

1894 - Piatti, Suite 1, Schott, Mainz

1899 - Zweigenit, Suites, Jurgenson, Moscow

1903 - Gruetzmacher, Bosworth, London

1911 - Schroeder, Suite 1 & 3, Schott, London

19?? - Carl Gardener, 6 Suites, Schweers & Haake, Bremen

EDITIONS for CLARINET

6 Suites arr. by Trent Kynasten. publisher: Advance Music

EDITIONS for TRUMPET

Cello Suites arr. by David Cooper. publisher: Roger Dean

6 Suites arranged by Andrew Kissling. publisher: AK Brass Press

EDITIONS for GUITAR (in preparation)

Already in 1905 the Paraguayan guitarist Agustin Mangore Barrios performed entire lute suites and also his own transcriptions from the cello suites for guitar.

Some 20 years later Andres Segovia transcribed several movements of the cello Suites encouraging many to follow.

Many guitarists felt compelled to add bass melodies, new harmonies to their own sport and leisure, making the cello suite sounding rather their own then Bach.

The most successful in this direction was the English transcriber John Duarte, although he never played his own transcriptions.Bach himself transcribed cello Suite No 5 as Lute Suite No 3, dedicated to Monsier Schuster.

_______________________________________________________________________

Here my version of an edition of Cello Suite 1 arranged for guitar:

_______________________________________________________________________THE MANUSCRIPTS

Considerations

Before going in the details of the 4 surviving manuscripts from the 18th century I like to mention a point regarding the psychological circumstances of the manuscripts in difference to prints.

The first kind of manuscripts were written for a person, often oneself or for a friend.

That means if it was oneself, of course the writer had in mind what was meant and often didn't bother to write everything in, some little mistakes were not corrected.

If it was written for a friend, you also could talk to them and say: here I wrote this slur, it was a mistake - but I mean this and that.

These kind of manuscripts can't be taken as a complete information. The additional conversations clearing up misunderstandings are missing and are allowed to be missing: they could be explained.

Publishing was never intended.

Today the manuscripts are treated as if every single note and slur is gold worth. At the time though the writer could have told their friend: Sorry about that line, there are mistakes in it, I was tired.

Then he/she explained and it was in both minds - copier and receiver - but never on paper.

The manuscript by Anna Magdalena's and Kellner's belong to this category of copies.

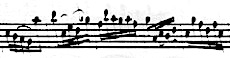

Prelude Suite 6, manuscript "D"

We can see the dynamic indications "po" for piano and "for" for forte.

Of course bar 1 has no indication (the forte is missing) although bar 2 indicates the echo. And why? Because in bar 1 there is not enough space above the slur of line 2.

You understand that, surely? So hopefully does everyone.

This manuscript here was by Kellner, the oldest manuscript. He was an organist, and probably wanted to play sometimes the Suites on the organ by himself.

We must though point out, that both Kellner and Anna Magdalena were not cellists.

That means, there was no need to add or correct anything, like a player would do, e.g correct bowings, when they don't work and also add some, because the indications are sparse .

Also there are no markings of fingerings.

There was a second reason for copying: collecting valued compositions by collectors of music.

These collectors collected whatever they could get hold of from composers they regarded as worth it.

Manuscript "C" and "D" stem from large collection of hundreds of pages, music for more than one instrument, impossible to have been all played by the collector.

The copying was probably done by paid copyists, e.g. manuscript "C" has been started by one copier and finished by a second one.

Unfortunately none of the probably many enthusiast's house copies have survived; very likely they have been superceded by easier to read prints.

Manuscripts "C" and "D" have rather survived, because they had not been used, and rested in unused collections - there is no sign of use like a fingering or corners missing.

More so, all 4 today known manuscripts are heavy books comprising all 6 Suiutes or even other works, too heavy to fit and be handled on a music stand.

None of the later prints are copies from "C" and "D" or Kellner and Anna Magdalena (see below the paragraph: Lost prints), but from either the original in case it still existed or lost manuscripts, who had certain details in common - which are different to the 4 surviving manuscripts.

We can't emphasize enough, that the manuscripts, which were used by cellists at the time, have not survived; not one manuscript with fingerings, personal notes has survived.

I discarded myself my oldest Bach printed copy, because I had corrected my fingerings so often, that holes in the paper started to appear.

Cellists must have been relieved, when printed copies arrived and they didn't need to rely on their heavily used copy, which up to then could only be replaced by many days of writing a new one.

Their copies are lost.

Rather because the surviving 4 manuscripts had not been used for playing, they were preserved for us in good shape.

In difference to Kellner and Anna Magdalena manuscripts C and D show in bowings and other details, that conscious effort had been made to think about options.

The originator(s) of their source (for manuscript "C" and "D" ) was likely a player, who had written one of the manuscripts, which didn't survive.

We must assume, that several cellists put their thoughts into how to play the Suites.

Moreover, it is likely that Bach himself went at different stages over the manuscript and changed his mind over some details, certain notes and bowings.

This is certainly the case for Anna Magdalena's manuscript.

Kellner copied likely from Bach's original, Anna Magdalena includes changes likely made by Johann Sebastian himself as I will explain in the chapter dedicated to her manuscript.

I wish to point out to the reader to take the early prints as serious in the question of originality as the 4 manuscripts.

These early prints relied on the used existing and now lost manuscripts or even the original in case it still existed.

These lost manuscripts and first prints circulated mainly within Leipzig, the city where Bach lived for the last decades of his life.

Of 16 prints published before 1900, 12 have been published in Leipzig and 4 in the rest of the world!

The reason for so many editions is quite likely, that the still existing copies had differcens and therefore there was a point to print again another edition

- and this edition would relieve the owner of the manuscript to hang on to it - the used copy could finally be discarded and replaced by a print.

Why would a cellist who anyway writes his own fingerings and corrections in - as we all do - not go for the best readable and clear source - meaning a printed edition - and throw the old handwritten messy copy finally out?

Summing up it looks like that the circulating copies at the time of the early prints have not survived and that the existing manuscripts have not been seen or consulted for the early prints.

I will prove this fact in the "landmark comparison."

This would mean that our 4 manuscripts today, which we are so proud of and take them as a gospel - may not be the closest to the original.

THE oldest MANUSCRIPT BY KELLNER (see also right column)

Kellner's manuscript is the earliest manuscript, written c 1726.

Kellner didn't play the cello or a string instrument. The cello suites are one of many manuscripts of works by J.S.Bach copied by Kellner.

Copied certainly from Bach's own copy - as Kellner copied also many other works from Bach's original.

It is of our interest, that the notes are as correct as can be.

The bowing aspect includes very likely also the ideas from the first original by Bach, but are treated without much understanding of playing a string instrument.

Unfortunately the whole subject of slurs, which is important to us today, is treated very casual - similar enough and giving a rough idea of what is written.

To read the slurs / bowings, one need to try to guess what was meant and what is error; which slur replicates the original idea, where is it forgotten, and where it is just placed - on the wrong spot or a slur of a similar but still incorrect length.

His bowings are even less consistent than Anna Magdalena's copy from a few years later.

Interesting is, that Suite 5 has no mention of the scordatura. It seems unlikely, that as a non cello player Kellner would have known where exactly to change the notes.

It opens up the question if the scordatura was a later idea. All other manuscripts are written with scordatura.

The Sarabande exists only of the first few bars, the following Gigue is omitted altogether.

THE MANUSCRIPT BY ANNA MAGDALENA BACH (see also right column)

Written c 1727-31.

Positives: Surely copied from Bach's original. Notes are very reliable, as original as can be.

Negatives: Anna Magdalena was not a string player. Bowings are often wrong, can't be taken too serious.

In general, as a singer Anna Magdalena thought in phrases, and if a phrase - e.g. marked with 3 slurs - seemed to sound nicer with 4, she wrote 4, although the bow direction would be messed up.

We also must not forget, that she did this work often after she had put to bed a part of 20 of Bach's children! We can only admire the amazing accuracy of notes and the peace and fluency in her writing considering the circumstances.

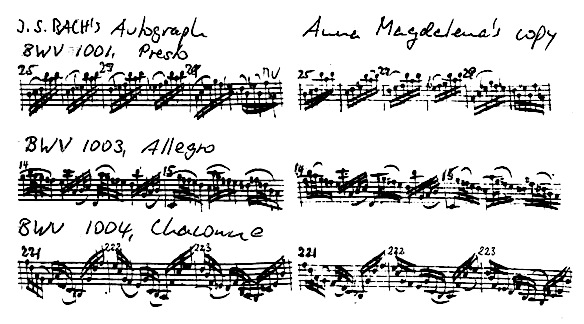

A Comparison of Bach's autograph and Anna Magdalena's copy in the Sonatas and Partitas for violin.

In these works both, Bach's autograph and Anna Magdalena's copy have survived and can give us an indication of her accuracy of copying.

The notes are 100% accurate.

The bowings are misunderstood, virtually neglected as a part of greater importance.

We can also see, how strict and consistent Bach's bowings are.

They consider the technical aspect and remain musically simple, repeat the main structure if possible to make sure, the character of the section is not disrupted by irregular bowings.

His attitude seemed to be: bowings need to be consistent; dynamics are expressed within the consistency (not as later C.P.E. Bach used complex slurs for expression, as mentioned below).

On quite some occasions Anna Magdalena shows complex bowings, but in difference to sometimes confusing bowings by her, these are consistent and ready to play.

They makes musical and technical sense.

She would not have invented complex and accurate versions of new bowings, different to the first manuscript.

We must assume she was instructed to change the first version.

One possibility could have been, with her husband Johann Sebastian next to her, he orally instructed her of the changes.

He was not fully happy with the result he had heard so far.

A second possibility could have been, J.S.Bach's son Carl Phillip Emmanuel might have put his ideas forward.

He was already an accomplished composer and is said to have been close to Anna Magdalena.

One reason to consider this option is, that e.g. the bowings in bar 1 - 4 of Suite 1 are logical, but irregular.

J.S.Bach loved simple bowings and does not show in his own manuscripts of the violin Sonatas and Partitas, that he uses complex bowings to express the music.

He goes not further than slurring piano passages and separating them in forte.

Carl Phillip Emmanuel though indulges in details rather than the broad picture, and the suggestions in Anna Magdalena's copy would fit his style.

But there is no evidence of any of the two possibilities, only that it is unlikely Anna Magdalena would have invented them in its accuracy.

As to the originality of this version, because no one at all referred to her bowings for 200 years, I assume also, Bach did not write these ideas anywhere else down;

he or his son just instructed Anna Magdalena, when she was writing down these passages and interfered to change them from the first draft.

The ideas were shelved in the manuscript until discovered much later.

Although most historians believe that Anna Magdalena is the most reliable source as she must have copied straight from the original of her husband no edition before Gruemmer (1944) bothers about her bowing (Alexanian published in 1929 her manuscript, but he did not consider her bowings. Her copy was treated ratehr like a matter of interest.

This is truly a miracle and must be explained.

I believe the reason is that her copies remained unused in a private collection.

Bach must have not written a second draft including the changes he or his son proposed in her manuscript.

WAS ANNA MAGDALENA THE WRITER OF THE BACH CELLO SUITES?

The author Martin Jarvis believed, that Anna Magdalena was not a copier of the cello Suites, but the composer.

Martin Jarvis wrote his book according to Eric Siblin based on studies by Esther Meynell.

The idea is based on the fact, that the original of J.S. Bach is not known.

We are all a bit lost with this fact and wish it would be found or exists.

The hunger for an answer is in the mind of many admirers of the cello suites.

Well, perhaps Johann Sebastian's original never existed and an answer is there! This is the basic idea.

Anna Magdalena displays in her copy a similar style of handwriting as J.S., beautiful and flowing, which made the idea of her as a composer interesting.The positives to the idea:

I think many cello students and players of the Suites are going through a stage, when they considered this thought and I am one of them.

The thought is attractive, seems surprising and original, because it is not the main stream belief.

Also because it is a surprising and common thought, it is a well saleable item and talk about idea.

The idea certainly comes up, because today her manuscript is usually taken as the main source.

The positives supporting the idea are:

Her hand writing is similar to Johann Sebastian's, beautifully flowing, unusually beautiful for just a copy.

Also the cello Suites have at some places a different style than the Violin Sonatas and Partitas.Why is it then not possible?

1) Firstly, Bach always acknowledged when he took material from someone else, like in the Notebook for Anna Magdalena he took pieces from his sons. He never claimed he wrote them.

(Only us today ignore Bach's acknowledgement; like Petzold's Menuet's and Musette are often printed as Bach's, but he never claimed them)

2) We have an original manuscript of Suite No 5 by J.S.Bach , transcribed for lute. It has Bach's signature. He would never have claimed the work, if it wouldn't have been his.

He would have referred to Anna Magdalena as the writer and himself as the arranger as he did so with work's by Vivaldi, Gerhard or his sons.

3) Her copy of the cello Suites is exactly in the style and part of the same collection as of other works by J.S.Bach, where we have the original, like the Sonatas and Partitas for violin solo.

Anna Magdalena's collection written for Schwanenberger became separated only in 1774.

Bach's Sonatas and Partitas for violin are called "Part 1" in Anna Magdalen's copy book, Part 2 is missing - the missing cello suites, her copy of Bach's work, same paper.

4) Also Anna Magdalena herself referred to Johann Sebastain as the composer. She copied exactly in the same style as in her copies of the violion Sonatas and Partitas.

Also her 'beautiful flow' of writing is exactly the same as in her writing of the violin works.

5) Her mistakes are of the same type as in the violin Sonatas and Partitas.

6) It appears, that no one ever knew Anna Magdalena's copy until it was displayed in a museum!

At the time no one copied from her. It appears her version was unknown.

Not one of the later copiers took notice of her mistakes - or originals - of bowings of either the cello suites or the violin Sonatas and partitas.

This would mean that all other copiers either ignored the composer or no one knew the original source, which doesn't make sense!

It would also mean, that Anna Magdalena stuffed her own creation just together with a copy of her husbands work for violin and didn't bother to put any effort into making them known.

7)Even if the year of origin is not clear , her copy varies e.g in Prelude 1 from all others, so it looks like her copy is already an alteration from the first draft.

8) It would mean that all other copiers followed some anonymous copier, and this copier disregarded the composer, but contradictory admired the work so much, that he copied it.

9) If she would have been the composer, the first source, other sources would exist more similar or even identical to her "copy".

10) As to the style:

It is rather a compliment to Bach that he writes for the cello differently than for the violin. The cello is not a violin.

I find it is strange to limit the idea what Bach himself could have written to a narrow spectrum of style, which is defined by some later historian, which would exclude the cello suites.

I would judge that the researcher who came up with the idea has an incomplete view of Bach's variety of styles.

There are certainly too many elements very typical for Bach as that any other composer would have written the cello suites.

It seems also that Anna Magdalenas image of her as a composer leaves unfortunately no room for her own style - except very similar to Bach, no identfyable personal style.

Despite that the idea to invent Anna Magadalena as a composer seems to be kind to her or flattering, I find the evidence of a lack of her own style makes the idea less kind.

The cello suites include "sister" pieces of movements in other works, which are too similar as not to stem from the same composer.

For example:

Prelude 1 from the cello suites is a "sister" piece to Prelude 1 from the Well tempered Klavier.

Bourree 1 of cello Suite 3 is extremely similar to the Bourree of lute Suite 1.

Courante of Suite 5 is extremely similar to the Courante of lute Suite 1.

etc. etc.

Also Bach called the solo works for violin Sonatas and Partitas, where as we have here cello SUITES. He certainly wanted to make a distinction in style!

It is mentioned by Jarvis, that he feels, the cello suites are inferior to Bach's superb style.

I disagree to the fullest - many refer to the cello suites as one of the most superb masterworks in history and Bach's most superb work - the part I don't understand at all is, why then Jarvis focusses on a work, which he finds weak.

This is the more sad, as many musicians and researchers find the cello Suites a very strong work.

But must admit, that at certain points a certain awkwardness in the bass melody lines seems to exist.

I always found this so surprising, that it made me think about it.

Why would Bach write a bass line, which does not flow so naturally than in his other works?

Bach didn't compose a weak element without reason.

I came to the conclusion that the reason would not lie in Bach, but rather in the cellists of the time.

As I will point out in the Sarabandes it seems, Bach didn't have a full confidence in the cellist's intonation.

He compromised, giving up the elegance of the melodic bass line in order to use as many open strings as possible, and also give up the clear line and take refuge to notes easier accessable one octave higher or lower.

We find this characteric "jumping" of intervals to an open string particularly in Suite 1.

We can observe a growing confidence in counterpoint writing by Bach in the Suites going through from Suite 1 to 6, as it looks like that his confidence into the cellist's capability has grown during the writing of the Suites possibly influenced by better cellists moving in from Berlin.

Summary:

If Anna Magdalena wouldin fact have been the composer, it would look like this ......

If she would have been in fact the writer, it would mean, that absurdedly everyone would have ignored her, that then mysteriously all others copied from a copier, who just chad hanged things, and mysteriously everyone ignored her and evryone took to this copier and everyone said it was Johann Sebastian's work, even the earliest copier Kellner.

Or Anna Magdalena would have written another copy of her own composition still with all the mistakes, which are typical for someone, who doesn't play a string instrument, and then this copy would have again been filed away so no one sees it, and no one knows.

And still everyone followed this mysterious copy of someone who does understand the cello and corrected it exactly in a manner which looks like Johann Sebastian would have written it!

It would mean the original would have had no influence what so ever until in the 20th century.

In her copies of the Sonatas and Partitas for violin she shows also, that she doesn't understand string bowings. She makes exactly the same mistakes as in the cello suites.

If we play her copy through, we always end up in the wrong bow direction; she did not understand the necessity of observing strictly even and odd numbers of strokes in string bowing.

this is essential and unique to string players.

There are other details she did exactly correct.

But how as a person who doesn't play a string instrument would she have known the possible and impossible, the comfortable and uncomfortable for string players?

Anna Magdalena was a singer and had obviously never played a string instrument.

The idea that she could have written Suites for a string instrument, which are playable and don't offend the technique of a string player is absurd.

A person not playing a string instrument would certainly have written passages impossible to play.

I think this argument is so strong, impossible to ignore and it would be the main reason against her being the composer:

A point to the originators of the idea:

As a singer Anna Magdalena would have much more likely have been inclined to compose a work for soprano and harpsichord, which she understood or a choral work, but never a work for strings.

I feel also, that the whole idea, that a singer sits down and writes a great work for cello, demonstrates rather more than anything else an unfamiliarity with the whole process of composing by the originators of the idea.

Every composer without exception started off wrirting for their own instrument or an instruments they intimately knew.

The creative impulse is driven by the idea that one could write something down which makes sense. This is a security, how it would sound and how it is done.

A composer is also following an urge to produce something of quality for generations after or for friends, who would acknowledge, enjoy and play the work.

But there is no record of anyone - by anyone - who would have followed her or it was written for or who would have collaborated.

To write a first composition for an unfamiliar instrument would require even for the greatest composer collaboration with a competent soloist of this instrument, proof reading and co editing, and would probably still be awkward.

Writing for an alien instrument requires a high degree of competence and experience form the composer. Composers like Brahms and Britten, where history was able to supply us with all the detalis, never did it!

Surely any collaboration would have resulted in correcting her bowings.

Also there would exist some local knowledge, that she wrote the work, who plyed it - people wopuld have talked about it. People copied it - of course they would have talked about it, known.

Even Johann Sebastian never wrote an opera as he didn't have actors and the appropriate orchestra to put any opera composition into practice.

How unlikely Anna Magdalena would have gone against all evidence of experience by all people surrounding her, against her surely conscious shortcomings and then she would write a composition void of own style - in just her husbands style.The more likely scenario:

The most plausible scenario would be, that Anna Magdalena was a copier, that she made a copy with bowing mistakes and other differences to other copies due to probably be surevised by Johann Sebastian, like a second edition. Like usual this applies mostly to the very first piece, Prelude from Suite 1. Probably - as it happens - as keen as he was, after the first few pages he got side tracked and turned to other matters.

This copy was shelved, and the other copies were made from Johann Sebastian's original with more correct bowings.

We should keep in mind though and admire how few mistakes Anna Magdalena made considering she wasn't a string player and also that she copied her husbands works in the evening after having put to bed quite a number of Bach's 20 children!

I feel this fact gives her much more honour than assuming that she was the composer, who wrote a weaker work than her husband.

Continuing the history of the manuscripts, after the original was lost, several versions coexisted side by side with small incongruences, as no one knew now what was right or wrong.

But no one referred to her manuscript because it was shelved away and not being the composer she was not the point of attention.

That there was no attention at all to her copy can be shown in that the first print to refer to the Bb in bar 26 of Prelude 1 - as in her copy - appeared in 1898, 170 years after her manuscript was written.

The first one to refer to her bowings (but ignoring them) was Alexanian in 1929, 200 years after she had written her manuscript.

For 170 years no one seemed to mind, seemed to care - and today no one plays her version, because not only it feels awkward, also she is alone with her bowings against the other prints and manuscripts.

Most likely: Anna Magdalena's copy is correct in the notes, as she was an accurate copier.

As a good singer she could probably imagine the melody when she wrote - and therefore her fluent style and virtually no mistakes in the notes.

As with bowings, in her mind bowings were an enigma, because the same way of indicating is used in her own music - singing, and instead of bowings the slurs meant phrasing.

This is actaully muddled up in the Baroque period with phrasing bows anyway - not to mention that even Brahms, Beethoven up to Benjamin Britten have a habit to do that.

(please see also: THE EDITIONS OF THE 6 CELLO SUITES IN HISTORICAL ORDER (85 Editions)- see right column or click here)

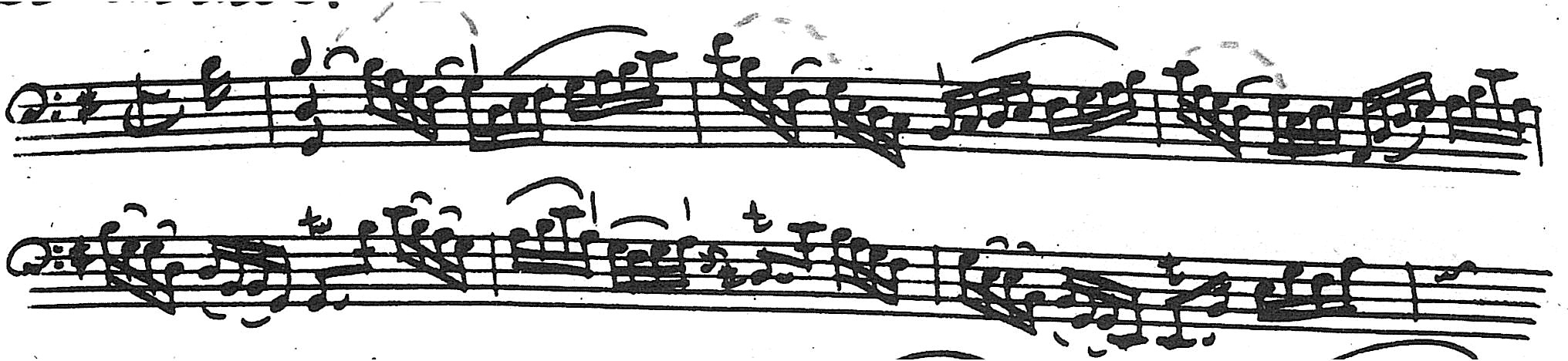

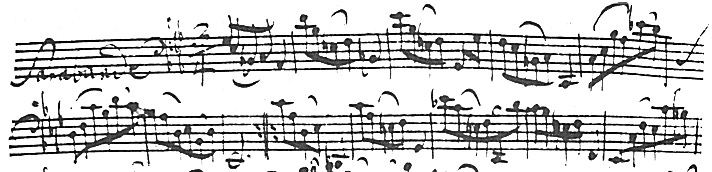

MANUSCRIPT "C" (see also right column)

Written between 1750 - 1800, but assumed to be older than manuscript "D".

The first writer of the manuscript (start to Bourree of Suite 3) is very logical, the text looks like written by a cellist, who has played the work or copied very well from a manuscript of a cellist.

The second copier is not that accurate, the music looks like written in a rush. We find often overlapping slurs etc.

The value of this manuscript (and "D") lies in the fact that it includes ideas of ornaments, which only a player of the Suites could have added.

Like manuscript "D" it was written during a time period, where performers started to play only the ornaments, which were written down.

This required from the cellists, who knew what was common to play, to write these ideas in. Manuscript "C" and "D" are from this point of view very important sources.

Nevertheless the copy was done for a collector, and was not the base of any early print.

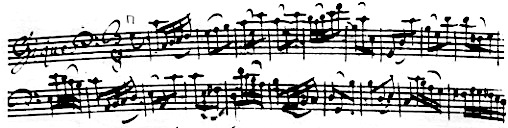

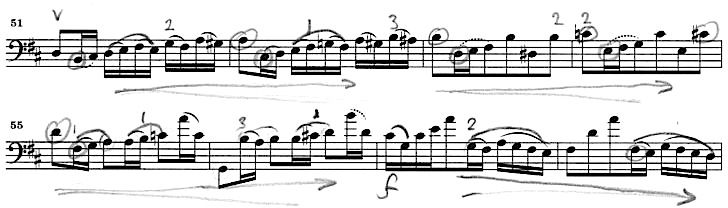

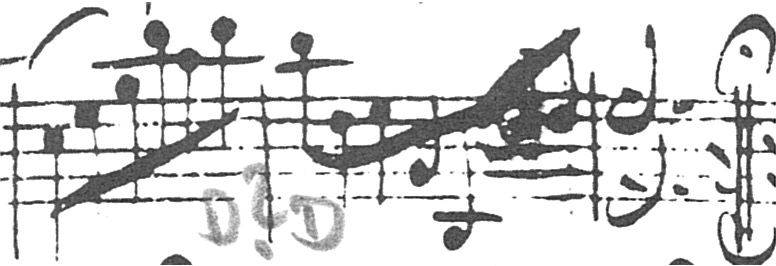

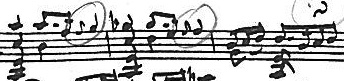

Bourree 1 of Suite 3 by manuscript "C - 1 & 2".

Copier "C1" is the writer from the start of Suite 1 to the penciled line, a clear writer.

The manuscript looks to me as written by a knowing person, a cellist, who played the works and included ornaments.

Had he been asked to copy his own manuscript for this collection, got other work and someone else was paid to finish the job?

Copier "C2" wrote from the double pencilled line to the end of Suite 6. His writing is rushed, bowings are often out by 1/8.

To me it looks very much, that the writer was paid a set fee to do the job, so he did it fast.

Not unlikely he was keen to have more work - like copying on order the 6 Suites from the manuscript of C1 for more customers.

Was he maybe the originator of hundreds of years of mistakes caused by his rushing (?), like the slur shift in Gigue 1- prominent in all early prints and in no manuscript - which looks very typical for his writing.MANUSCRIPT "D"

Written c 1775 - 1800.

Similar to manuscript "C", written for a collector of Bach's music.

As manuscript "C" this manuscripts was not used as a base for early prints.

However, there are similarities to the first print of Cotelle, more than in the other manuscripts.

For example it is the only edition, which suggests to slur in the first 4 bars of Prelude G major 4/16, as we see it in Cotelle.

The copier was less tidy than "C" and less consistent.

The ornaments in both manuscripts are virtually identical.

In difference to A and B this copier was certainly a cellist. Taken into account that he wrote very quickly - because it was just a job for a collector and not a player -

and also because rubbers and white out didn't exist, the writer left bowings in, which he wrote by mistake and also wrote them often too short.

Taken this into account, this edition can just be played and sounds good and interesting and the bowings, which sound firstly too free or not systematic,

sound actually very well and make muscial sense. Also one doesn't get stuck at the wrong end of the bow, because the writer doesn't understand the logic of up and down bow. This copier did!

The writer has certainly played the suites and new how it would sond when he wrote the boeings in, and also the differing notes from other manuscripts.

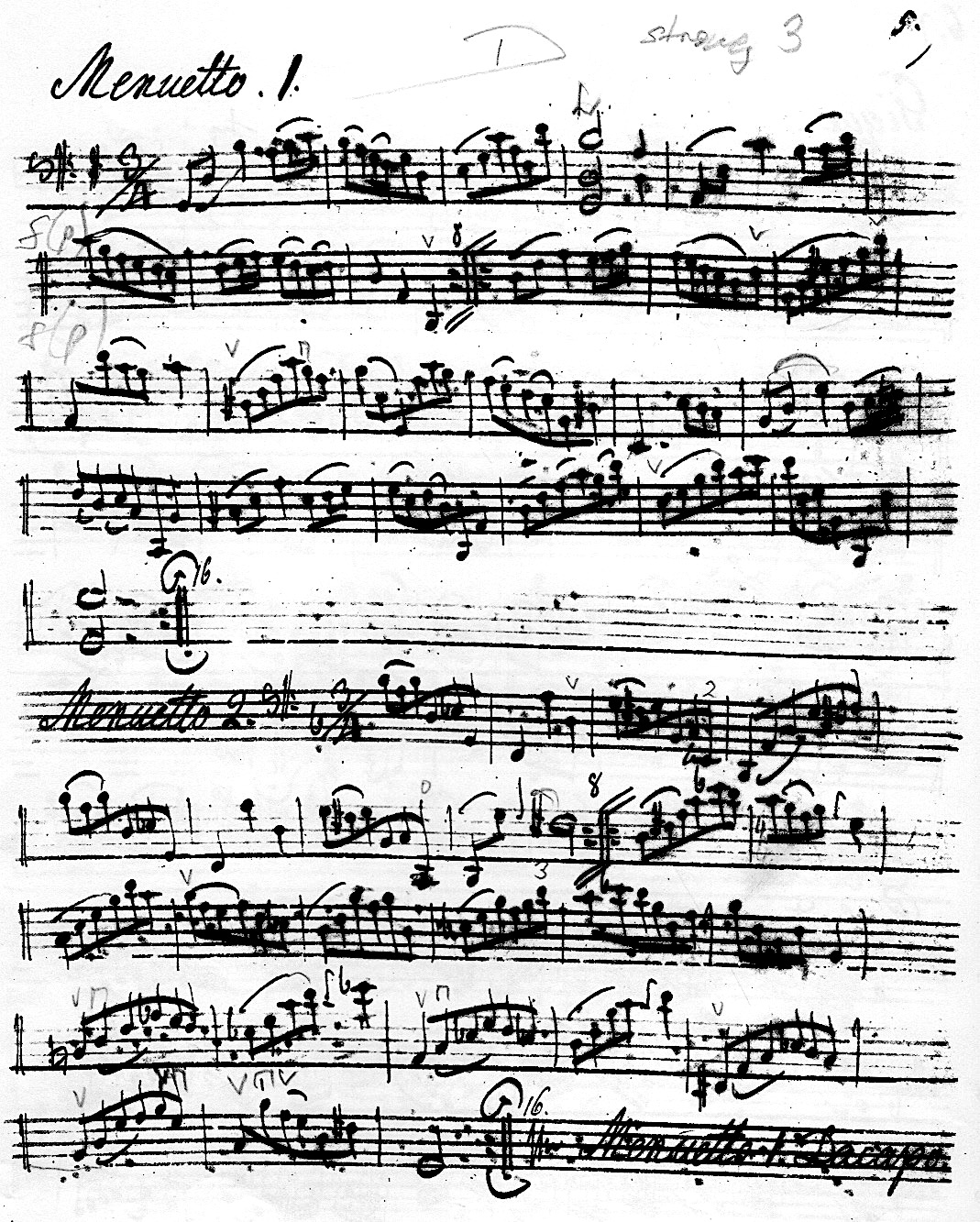

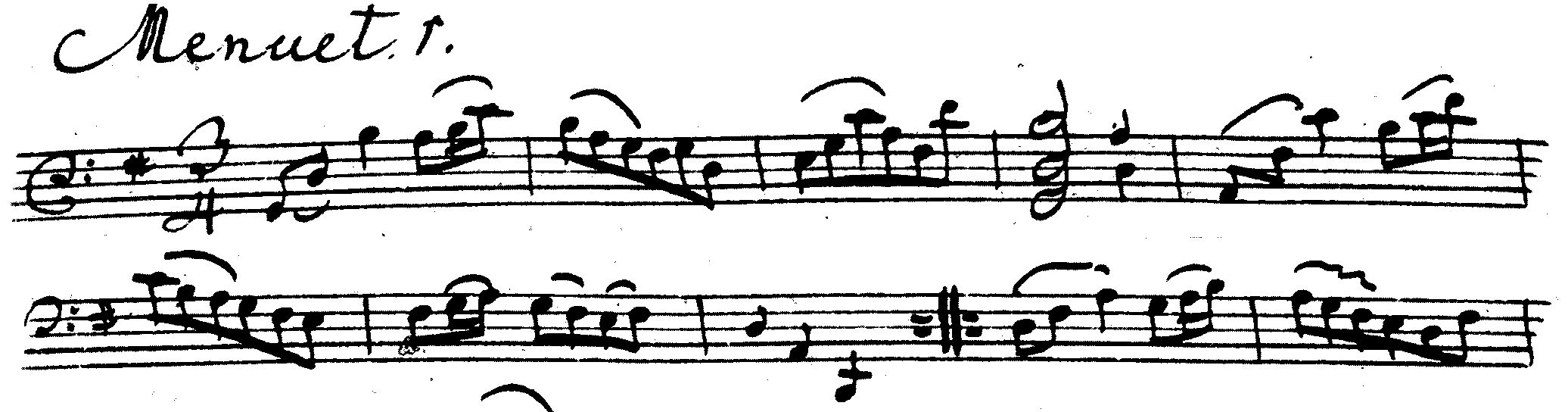

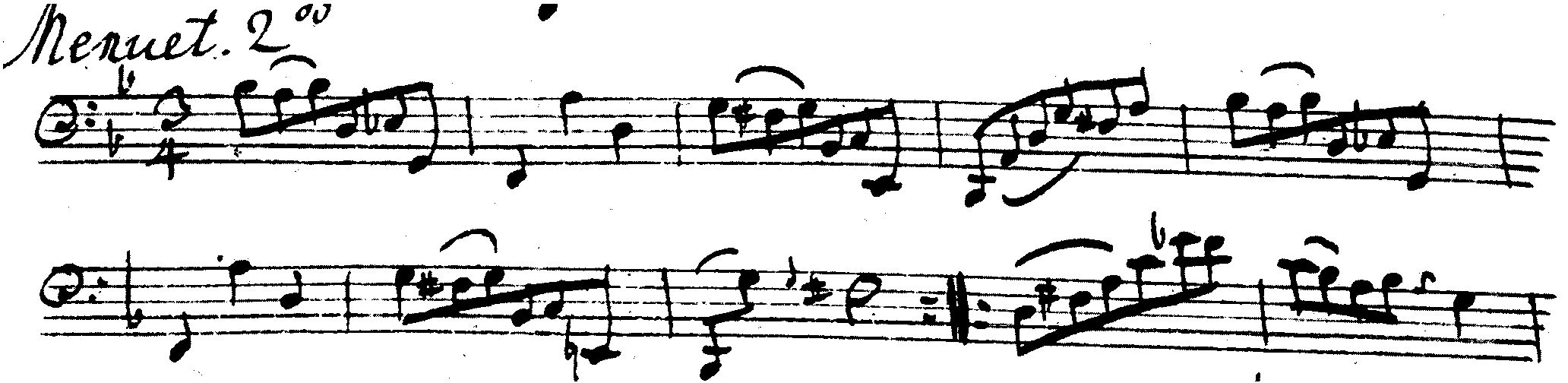

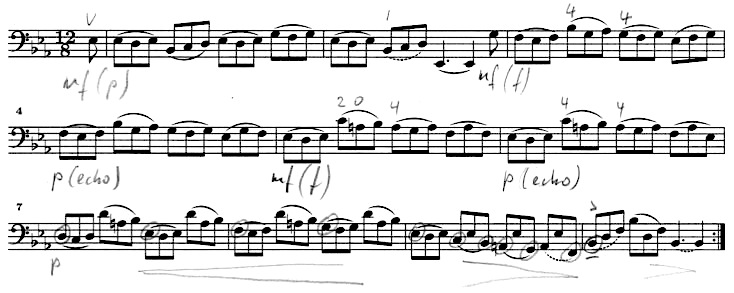

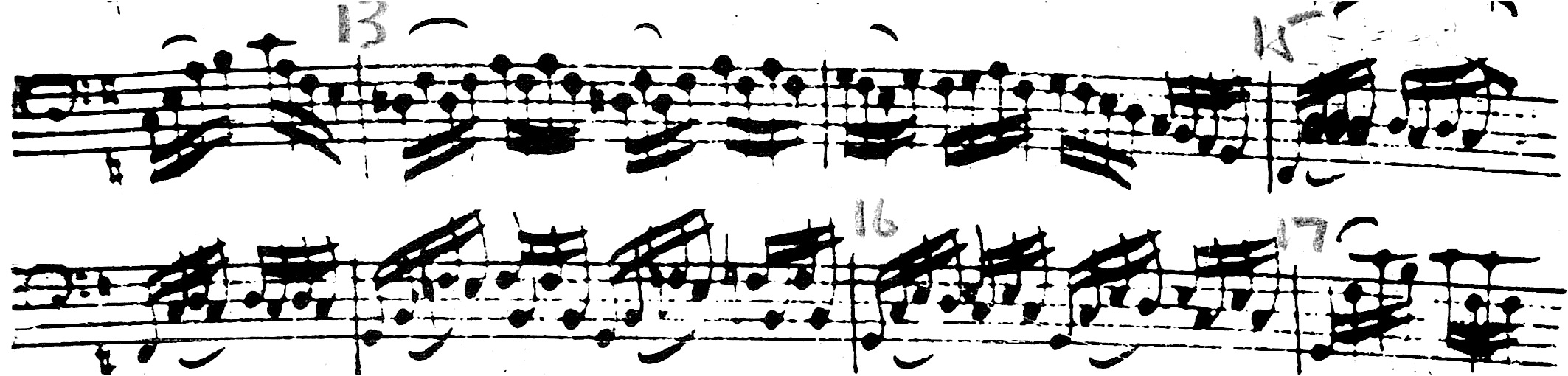

Here is a copy of the Menuets of Suite 1 including my few extensions and corrections of bowings:

Here a Youtube clip of the Menuets:

LOST Manuscripts

We must assume, that the circulating copies at the time of the early prints have not survived and that the existing manuscripts have not been seen or consulted for the early prints.

I will prove this fact in the "landmark comparison."

This would mean that our 4 manuscripts today, which we are so proud of have not to be taken as a gospel, are not necessarily closest to the original.

The question how many manuscripts Bach has written and what he actually wrote is still open after comparing the manuscripts and we need to extend our research to include the early prints.The first prints of Dotzauer and the Cotelle edition share interesting parallels in certain inaccuracies, e.g. the Bb in bar 26 of Prelude 1 or the syncopation in bar 1 of the Gigue of Suite 1.

This common mistakes (?) hint a common source of a manuscript they both had copies from - an enthusiast, who made multiple copies, and copies were made from these.

Both editions are not following closely any of the 4 early manuscripts known today.PRINTS

Prints are meant to be read by the unknown person. All information needs to be included in the print.

But there seems to be a certain regular mishap in first prints: They are often printed in a rush to get the publication out.

If you ever published something or know someone who has, they will tell you of the magic moment of opening the brand new print and your eye is somehow instantly attracted to a misprint!

Although first editions are often more valuable, second editions have less mistakes.As mentioned above, the earliest print by Cotelle is impossible to play through without a correcting pencil in the hand: the bow ends up always in the wrong direction.

For me it looks as if the publisher was (quite naturally) no string player, and the editing cellist had for some reason not done the proof reading.

Supposed the well known cellist by the name of M. Norblin prepared the edition (the cellist & composer Jacques Offenbach chose him in his final years of studying).

I can't imagine he would have certain passages let go through without saying: No, that's wrong.

(Maybe or very likely Norblin picked up a copy from Dotzauer - it has been recorded that he travelled especially to Leipzig to obtain a copy; or he quickly wrote a copy himself.

Norblin probably knew, that Dotzauer was about to publish his edition and wanted to be first, and therefore the Cotelle - Norblin edition was terribly rushed).

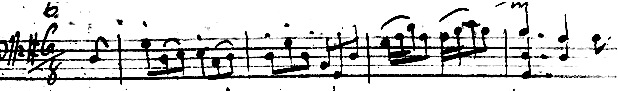

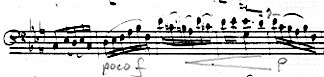

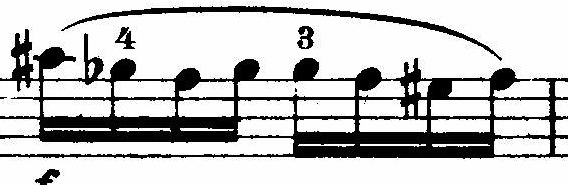

A good example for lack of proof reading is the misreading based on a right shift in the Menuet of Suite 1 (see below)

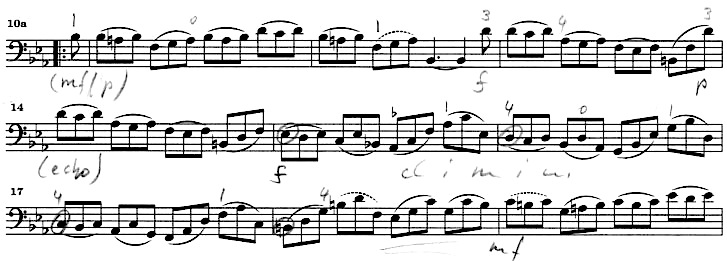

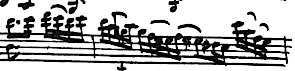

First print by Cotelle misinterpreting the handwriting showing a right shift in the bowings - here bar 5 - 9: bar 5 of the Menuet I has an incorrect bowing,

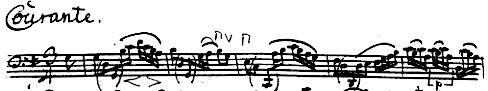

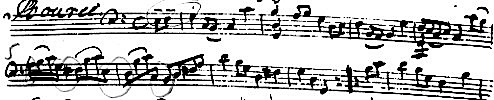

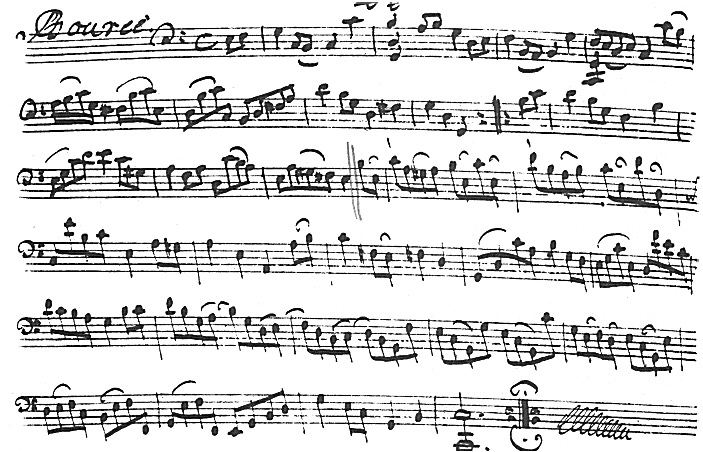

misread because of the right shift and in bar 9 - same figure - the correct bowing.The title "Loure" in Cotelle's print for the "Bourree's

The title "Loure" for the Bourree's might in my opinion also be based on bad handwriting:

Bourree was frequently written without double "r" and sometimes also only with one "e" (as in 3 readings of 4 in manuscript "D").

If the "B" was written in a rush - the editor had problems with the handwriting presented, from "Boure" from "Loure" is not far fetched.

A Loure is such a different kind of dance (a slow dance in 6), it doesn't make sense.

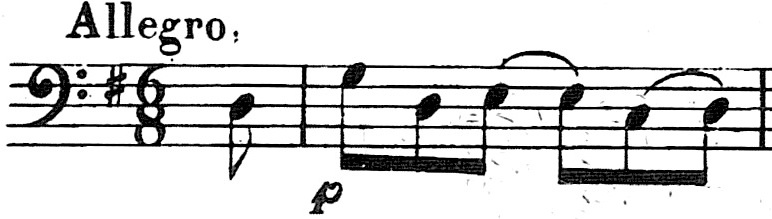

Again: Norblin would have picked the mistake - and probably wished he never agreed to the publication without having seen it!Dotzauer's first edition

Virtually at the same time the first Dotzauer edition appeared.

Dotzauer obviously had more input in his edition. There are very few mistakes and are corrected in the later edition.

The bowings are clear and logical, even if we don't agree. His edition was so convincing it had reprints for at least 130 years.

Cotelle's edition did not have a second print run.

Cotelle's edition became romanticized, because Pablo Casals discovered the Suites through this edition, bought second hand in an antique shop.

This story received new fuel through Eric Siblin's book on the Cello Suites.

Strangely no one mentions that Casals did not use Cotelle's edition later. His performances rely on Dotzauer, Gruetzmacher, Doerffel and Hausmann.

He must have found as well, that Cotelle's edition was poor.I compiled in the right column all editions I could get information on in historical order. 85 are listed here and there exist maybe a few more.

There are links to historical editions available on line - today public domain.

Groups of Print EditionsThere are several "groups" of print editions.

To the first group belong the early editions like Dotzauer, concerned with a balance of firstly faithfulness to the original if known to them or surviving manuscripts and secondly practicality, that bowings are consistent so one can play through the Suites in an enjoyable fluent way.

These editions include fingerings and often tempo recommendations as well as some ornaments and sometimes dynamics.

Until today most editions are concerned with the balance of faithfulness and practicality.The next group is more concerned with faithfulness than practicality.

In these editions we find e.g. inconsistent bowings, because they would not dare to write bowings, which are not found in any manuscript.

Doerffel was the first of these editions. He tries to discover a system and applies the system he believes Bach's original might have shown, combined with literal faithfulness.

Gruemmer follows strictly Anna Magdalena.

Some editions - like Wenzinger - use for the faithful bowings solid slurs, for recommendations according to parallel logic or sheer practicality dotted slurs.

Similar are editions, which are keen to discover the systematic thinking. Their bowings follow this consistency.A small group of edition leave it up to the reader / player to write bowings in according their own taste and decisions. The first of these editions is Vandersall.

The new Baerenreiter edition fits also in this group: It delivers the early manuscripts and offers the music ready for the player to write their own conclusions in.Another group starting with Becker is just concerned with the effectiveness in performance. Faithfulness plays a secondary role, if any at all.

Becker was the first to recreate all bowings following Gruetzmacher, who paved the way not daring yet to do away completely with original bowings.

Interestingly enough Becker's edition, with no attempt to be faithful or capture the character of the dances, became the most popular way of playing the Bach Suites.

This is surprising as Becker doesn't even attempt to get the style right; he just wants effect.

E.g. Starker followed his way with different own ideas.A last category I call the "intellectual approach". It was felt by some teachers, that the bare notes and bowings don't explain the complexity of the composition sufficiently.

They included added notations, staves, overlapping lines, arrows and comments to show how they imagine Bach might have thought.

The earliest is by Diran Alexanian - difficult to read, sometimes virtually impossible to find one's way through.

Alexanian is interesting in the point, that the edition looks very 'intellectual', complicated.

It is like an interpretation of poetry by someone who uses a complicated language and rare words.

However, there is no clarity in structure, no consideration of natural or Baroque bowing (not even Anna Magdalena's, whose manuscript he includes);

it looks like made difficult without answering the question why.

Alexanian goes so far to ignore original notation; he puts his personal version forward, unfortunately unexplained.

On a positive side, he is the first to include the manuscript of Anna Magdalena for reference in his edition.

Following the same idea is Enrico Mainardi, who writes the whole Suites in two systems, explaining the counterpoint in the lower system by using up and down stems.

He makes the reader aware of the parts, it is easy to read, although sometimes he pulls melodies apart just to make use of his double stems.

Mainardi like his teacher Backer does not care much about the original, as if an intellectual pull apart is superior to going through the original slurs and phrases.

On the positive side (it was my first edition), he makes the less musically trained player aware of the possible complexity, the polyphony, behind the plain notes.

I asked for permission to offer p1 of the edition as an example.

Unfortunately the new owner of this Schott edition, Hal Leonard, wanted to charge me more than $100 for showing this one page edited 1941!

The third edition is by Paul Tortellier. We find overlapping slurs and arrows from different sides in an attempt to visualize the complexity of polyphony.

I listened to his recording with his copy in my hand and gave the copy away shortly later, as his own playing unfortunately neglected and contradicted his drawings.

Quite recently a Casals edition has been published by Madame Madeleine Foley.

I noted by surprise, that he used the same graphic methods as me to explain structure!

I developed this graphics for students with limited theoretical musical background: as simple and clear as possible.

In contrast to the 3 other editions reading his instructions can be followed easily:

the bass lines are circled note by note, so we can follow easily from one note to the next, even if they are bars apart.

Of all the intellectual editions, this edition gives us an easy insight; we can read through and follow the advice without stopping and studying the text.

Unfortunately some of the circles are missing and have not been added as a matter of completing, as if having taking the master too literally, when either he forgot a circle or thought one might now understand what he means.

(see above: the psychology of manuscripts; handwritten notes combined with talking are hardly ever complete, as talking may have completed the missing bits - or also, Casals might have wished to go on as the main idea seemed now clear).

Without doubt the Casals edition can add to the understanding of Bach's composition and the quality of the performance, even if we decide to play in a different way.

(I wished as an example to display page 1 of the edition, but unfortunately the publisher did not bother to respond to my request).

A "LANDMARKS" COMPARISON OF THE EARLY SOURCES

I will attempt to demonstrate a certain logical sequence of the early sources by comparing some "landmarks".

Many other 'landmarks' could have been picked.

My aim is not to pick the differences here, but to disprove the theory, that one copier called "G" was in between Anna Magdalena / Kellner and the subsequent sources of manuscript "C", "D" and Cotelle's first print.

This theory can't stand up by comparing just 2 landmarks.

The landmarks I choose are:

A - Bar 26 of Prelude, Suite 1

B - Bar 1 of Gigue, Suite 1A - To Bar 26 of Prelude, Suite 1

I select firstly bar 26 of Prelude 1.

As shown, all 4 manuscripts show a B natural, all prints Bb for the 2nd 1/16 in the selected section.

We must assume, that the original by Bach showed B natural.

How would it happen, that all prints show Bb?

The first notion is: no early print copied from one of the 4 known manuscripts. They copied faithfully and consistently from other sources.

We have not to forget, that Bach's original was already known as to be lost. Early collectors as early as 1800 like Forkel, Poellschau and Doerffel had the common knowledge, that Bach's original of the cello suites was lost.

Anna Magdalena's copy seemed to be locked away - no printed version shows knowledge of it.

Cellists and printers were confronted with different versions of manuscripts; there was no logical reason to give more preference to one or another.

The decision over time was made according to how people got to know the Suites; the way it was most commonly played, seemed the most true one (see below the hand correction in Hausmann's edition).I need to mention here the power of performances of exceptional musicians.

In our life we are a few times moved by performances of music. Virtually always this experience is linked to an exceptional performer.

Like every human, this performer relies on the resources available. If the notes or bowings are correct or not, once performed in a superb way, they gain power.

If a misprint happens to fall in the hands of an exceptional performer, the misprint turns into a desirable version: everyone wants to play like that.

There are so many ways to interpret and so many ways of music, if the performance is exceptional, this variety will be the desirable one until superseded by an as exceptional performance;

in our search for truth we rely instinctively rather in the conviction of the performance than in the correct notes.

The truth of music does not consist in written notes, but in the sound they would produce. The structure in the music is only valuable, when we can hear it.

The real truth lies in the performance or in the life reproduction of any player.

Therefore a change of notes in a major work, which has been performed hundreds of times will only convince, once the version with the change has been performed convincingly.The most likely train of thought seems for me, that an enthusiastic performer did multiple copies (perhaps already from a copy), likely a well known teacher with many students;

this version was then spread among growing professionals in the area of origin, Leipzig.

All printed versions stem form copies.

That means, all prints stem from manuscripts, which have not survived.

These unknown manuscripts were more popular than our 4 known ones.

More so, none of the prints is a copy of the 4 manuscripts.

Changes happened on the way by copiers unknown.

As to our bar 26: We cannot assume, that a note was altered by purpose.

We can see though in the way of the bowings are drawn, that many copiers followed the order: firslyt the notes were written, secondly the additions like accidentals and slurs.

The writers went back with the hand to write any additions to the heads and stems.

Some of the copiers wrote obviously in a rush (see the 2nd writer of manuscript "C" in Bourree 2 of Suite 3). Slurs shifted to one note too far left or right, accidentals were quickly written in.

In our case here the b was placed in front of the correct note in the correct bar, but at the wrong place - a likely place for a mistake ( I assume exactly the same happened with the bowings in the Gigue of Suite 1 as shown below).

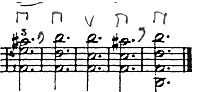

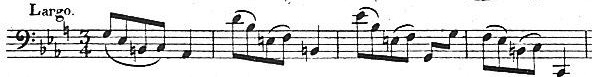

All 4 manuscripts ("D", c 1775-1800):- All prints before 1898 (here Dotzauer 1890):

Hausmann 1898:

As we can see in the Hausmann copy as shown in Petrucci, one of the owners of the copy corrected this first version of the B natural back to Bb, as if it was a mistake!

For all what the owner knew, all known prints differred, and the manuscripts were unknown.

(Pablo Casals played B natural, and so does Tortellier, who frequently played with Casals together; Casals student Alexanian was the first to publish Anna Magdalena's manuscript in print.

We don't know, what Casals played before, as his surviving recordings are from a later date. Most performers to today including Rostropovich, YoYo Ma, Maisky play still Bb).B - Bar 1 of Gigue, Suite 1

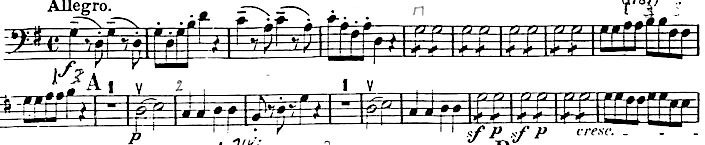

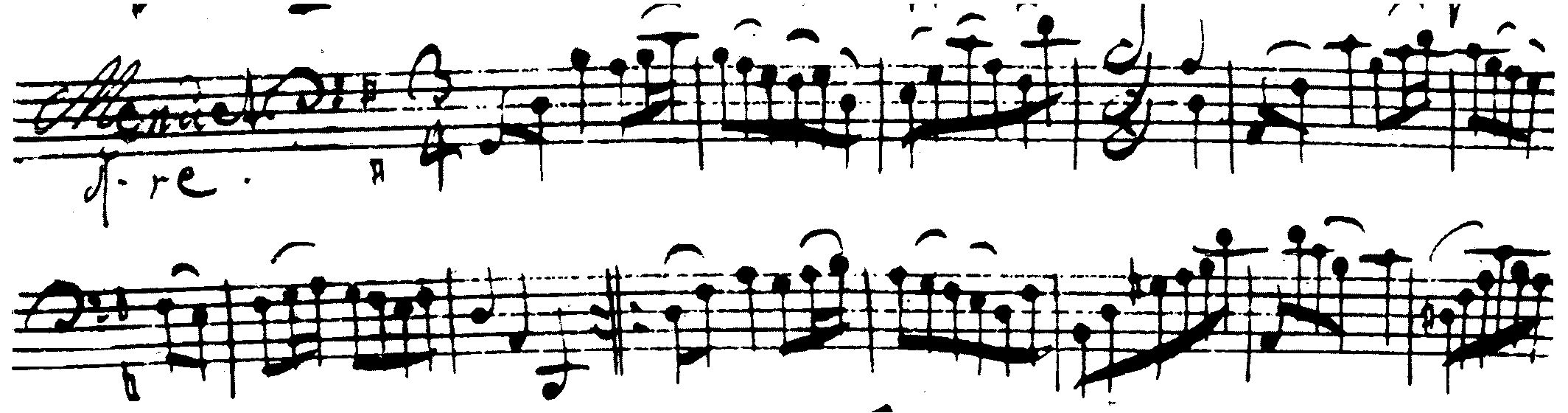

The same as in bar 26 of Prelude 1, all 4 manuscript give us the same reading in bar 1 of the Gigue: 1 single 1/8 followed by a slur of 2 (this pattern twice).

This must be the original version.

(left) all manuscripts show this bowing (here manuscript "D").

(right) all early prints show this bowing including Dotzauer (here "Cotelle")

As to the possible confusion see below the Menuet of Suite 1.We can't assume, that a cellist purposefully invented this very unusual syncopated bowing against Bach's original ideas.

The most like scenario is again, that a casually written copy showed a slur shift to the right.

The slur meant to be for the 2nd and 3rd 1/8 shifted to one 1/8 to the right, creating the syncopated rhythm.

This copy - I think must - became the master copy for many and it looks like it didn't meet any resistance but rather a liking.

We need to remember, that having knowingly no original to fall back on, all copies gained equal rights. The most liked one won.

Also as mentioned above, once the misprint - or miswriting - has been performed by an exceptional musician, it turned into the desirable version, even if it was factually wrong.

The first print to go back to the original version I found is the Bach Gesellschaft editor Doerffel in 1879 (private owner of the original of Bach's Sonatas and Partitas and a collector of Bach manuscripts).A POSSIBLE (DIFFERENT) GENESIS OF THE SUITES AND THE MANUSCRIPTS

(It is likely that before 1720 J.S Bach might have improvised sometimes on the cello, and gradually Prelude 1 took shape (see more about this idea in: Prelude 1).

The arrival of excellent string players including cellists sparked off the idea to write a larger work for cello or cello solo.

Bach is believed to have started to write the cello Suites around 1720.

At this stage Bach was not focused on choral work, but had an orchestra at his disposal including the new instrumentalist due to them having to have left Berlin, because the funds for the orchestra were used for military.

It was a perfect time to write instrumental challenging works with the perspective that they were played, perhaps even with certain players in mind.

The violin Sonatas and Partitas followed or were written simultaniously,

Already at an early stage, copies were made of the Suites, as this was the custom of the time. Not many composition made it to be printed.

Kellner's manuscript from c 1726 was part of a large collection including the cello and also violin solo works (he played organ, flute and lute), not used by cellists, perhaps just out of interest in his friends compositions. Kellner must have admired his friends talented and wanted to make sure, the compositions survived. The cello suites are on pages 249 to 275.

In this manuscript Suite No 5 is written for standard tuning, but the Sarabande is cut short and the Gigue omitted.

Between 1727 - 1731 Bach transcribed the cello suite No 5 for lute (Lute Suite No 3), dedicated to Monsieur Schouster. This is the only surviving Bach original of any "cello" suite.

(It is not impossible that the original before the transcription for lute was for standard tuning.

(It came into my mind, that it would not be an impossibility, that the scordatura was maybe introduced in order to hide the use of the B-A-C-H theme; see also the reference to the B-A-C-H theme in the analysis of Suite No 5).

Anna Magdalena copied the Suites in a set including the Violin Sonatas and Partitas c 1730 with noticeable changes of bowings / phrasing in many parts.

Either Bach had by this time written a second version or he supervised Anna Magdalena's copy in some parts, changing bowing and phrasing.

Simultaneously many cellists copied the Suites.

Very likely different "schools" of playing emerged. Strong musical personalities of teachers created different ways of playing the Suites, complimenting and changing the bowings, writing ornaments and also some dynamics in.

These different "schools" of playing were copied by hand by students and their students.

(This is a tradition to today: Independent of the copy I owned, I had to copy my teachers bowings and fingerings, which were Janos Starker's from the time period my teacher had been studying with him. All my study mates had to copy these markings from the "grand teacher". This is a very common tradition in the music world over centuries.)

1750 - 1800 Manuscript "C" and "D" copied for collectors of Bach's work.

These copies also had never been used to play from; no essential markings for cellists like fingerings and complimenting or changing bowings, no up or down bow marks, just no sign of use can be found.

The originals went the path of inheritance, landing in obscure hands, like the violin Sonatas and Partitas, and were at a quite early stage already regarded as lost.

The first prints emerged c 1824 - 1826.

The story goes that the French cellist M. Norblin travelled to Leipzig to get hold of a copy (or copied himself) of the Suites he had heard of.

At this stage Dotzauer had already emerged as a main figure in the cello teaching world (and is until today) and was in the process of preparing a first printed edition of the Suites.

Being in Leipzig he must have had access to virtually all varieties of copies available and studied them.

Norblin travelled back to France and pushed for an earlier edition. It looks like he didn't have even time to proof read the edition, as if he handed the manuscript and had the impression, that a print from his manuscript can't be too wrong and he gave the go ahead without reading through.

A very short time later Dotzauer's first edition appears.

Very likely the appearance of an easy to read edition with clear bowings and fingerings resulted in throwing out the worn out handwritten copies with markings and cross outs everywhere, or at least it was done by the next generation, because they were not used anymore.

For quite some time different copies still survived, or at least different opinions.

From 1824 - 1900 16 editions appeared worldwide, 12 of them in Leipzig, by Dotzauer, Doerffel, Schulz, Hausmann, Schroeder, Gruetzmacher and Klengel.

in my opinion this reflects the multitude of manuscripts and opinions being around Leipzig for more than 150 years.

Once all these opinions had appeared in print, the last hand written manuscripts used by cellists must have been seen as finally irrelevant and were thrown away.

The Suites in manuscript survived only in large collections by collectors out of fancy, which were not thrown away, because the books were large (some more than 400 pages) and clean.

CONCLUSION

We are used to focus our thinking on the one big secret: what would the original of Bach have looked like?

The traditional answer is to focus on the surviving manuscripts in time closest to the creation of the Suites.

But is this necessary the best and only answer?

I want to go through some interesting and unexpected thoughts, which might be surprising:

Firstly it is believed and likely that there are several "Bach originals", a first draft, "working copy", a later copy and perhaps an updated, changed copy.

Already there we don't have the truth, but several truths, and need to make similar decisions as with our 4 manuscripts.

As to the manuscript and prints I came to the following and probably very surprising conclusion:

Contrary to common believe I think no one ever consulted the known 4 manuscripts until the 20th century.

The first two manuscripts by Kellner and Anna Magdalena are not written by a string player.

Although they copy the notes faithfully - Anna magdalena nearly faultless, Kellner with a few more mistakes-l - they both fail to understand the nature of bowings for strings.

This is out of ignorance of string playing but also maybe carelessness because no one ever played from them and there may have been no likelyhood that a cellist would use these copies.

I believe some mistakes would have been corrected by the first person who read from them (like the missing ledger line in Menuet I, Suite 1 by Anna Magdalena).